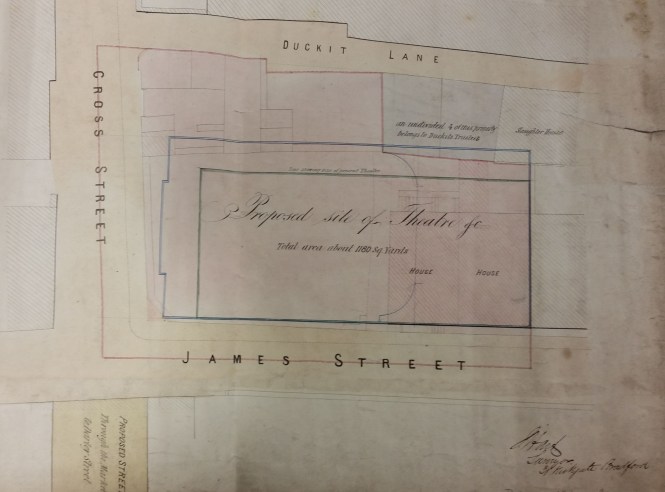

This map from the Local Studies Library reserve collection would seem to be the plan of a theatre or music hall drawn up prior to its enlargement. When I first saw it I recognised the location, between Duckett Lane and James Street, (which connect Godwin Street and John Street) but I could not see how a theatre could ever have been positioned there. I could not then have named a single Bradford theatre besides the Alhambra and the Star Music Hall. The Star had an important role during the great Manningham Mills strike of 1890/91 when its lessee, a Mr Pullan, placed his premises at the disposal of the strike committee during the early days of the dispute. In Charles Dickens’s rather neglected novel Hard Times Mr Sleary, a circus manager, says: ‘People must be amused…they can’t be always a working, nor yet they can’t be always a learning’. So, how were they amused in Bradford? In the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries itinerant entertainers visited public houses, and there were also visits from fairs and circuses. It appears that permanent theatre building had commenced by the 1840s.

The theatre in this plan was placed near Westgate and in 1849 Henry Pullan is known to have built the Coliseum Theatre ‘off Westgate’. However I cannot be sure that this map is actually of the Coliseum Theatre. Pullan had previously managed the Bermondsey Saloon in Cannon Street, a noted place of entertainment. His Coliseum was unusual in that it was not directly linked to a public house. Twenty years later he moved to a new theatre called Pullan’s ‘New’ Music Hall, Brunswick Place (now Rawson Street, by the multi-storey car park). This had an amazing 3,000 seats; the modern Alhambra has less than half that number. Pullen’s new musical hall remained in existence in the years 1869-89 at the end of which time it burned down. The vacant site left after the fire eventually evolved into John Street open market. Thomas Pullen and his son seem later to have taken over as managers of the Prince’s theatre and Star Music Hall, which brings us back to the Manningham Mills strike.

Although this plan was not dated it does mention St George’s Hall (opened 1853) and the New Exchange assembly rooms (foundation stone laid 1864), so presumably it was drawn after 1865. It seems plausible that it represented an intention to enlarge the old Coliseum theatre around 1868 although in the end a wholly new building was constructed on a nearby site. The older theatre evidently survived, being later renamed as St James’s Hall and then The Protestant Working Men’s Hall. It was finally demolished in 1892. This is a plausible date for the construction of the Commercial Inn still standing in James Street. This certainly looks like a late Victorian building.

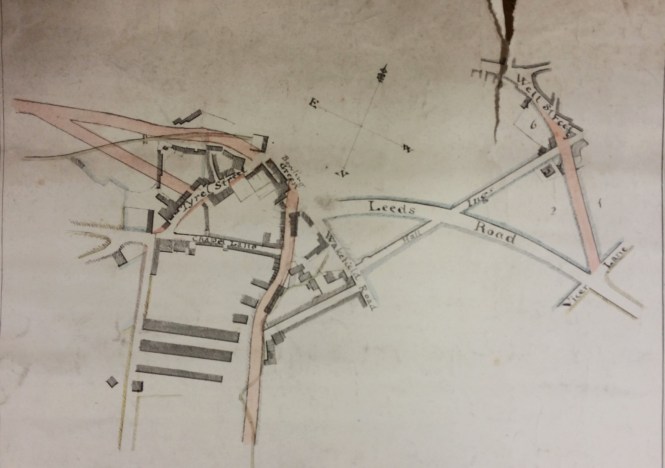

The Coliseum was not Bradford’s first theatre which is said to have been owned by an L.S. Thompson in a converted barn on Southgate (now Sackville Street) around 1810-25. This hosted travelling theatre troops. A few years later, in 1841, the New Theatre opened at the city end of Thornton Road using the upper room in an existing Oddfellows Hall which had been opened in 1839. The Oddfellows were a friendly society who had 39 branches in Bradford and surrounding areas. I understand that the New Theatre was intended to hold ‘superior performances’. In the same year the Liver Theatre, Duke Street, became Bradford’s first purpose built theatrical premises. In 1844 it was remodelled and re-opened as Theatre Royal, Duke Street. The fact that it was widely known as the ‘wooden box’ may say something about the standards of its construction but in illustrations it looks stable enough. In 1864 the Alexandra Theatre had opened in Manningham Lane but in 1869, when the original Theatre Royal finally found fell victim to a series of street improvements, the Alexandra took over its discarded name. The Theatre Royal’s moment of fame occurred in 1905 when the great actor Sir Henry Irving gave his final performance as Thomas Becket on its stage. Shortly afterwards he collapsed and died in Bradford’s Midland Hotel.

In 1876 the Prince’s Theatre was built above Star Music Hall in Victoria Square. The proprietor of this curious double establishment was entrepreneur William Morgan who started his career as a Bradford hand wool-comber and concluded it as mayor of Scarborough. I think its site is the garden that is now in front of the Media Museum. Both theatres were fire damaged and restored in 1878. The Star Music Hall was renamed as Palace Theatre in 1890s and finally demolished in the 1960s. In 1899 the Empire Theatre was built at the end of Great Horton Road. All three theatres were just across the road from the present Alhambra which was built in 1914 and is associated with the name of Bradford’s pantomime king, Francis Laidler. In 1930 the New Victoria was opened on an adjacent site but this was eventually converted to the iconic Odeon Cinema. Finally I should mention that in 1837 the Jowett Temperance Hall had been built and this was also converted into a cinema as early as 1910. This building was also destroyed by fire and was rebuilt in 1937 as the Bradford Playhouse, Chapel Street.

If you would like a more detailed, and very well written, introduction to the subject of our theatres there is a splendid website:

http://www.arthurlloyd.co.uk/BradfordTheatresIndex.htm

A long account of the theatres is given in William Scruton’s Pen & Pencil Pictures of Old Bradford. Scruton provides many details of the largely forgotten actors who performed in Bradford. More recently the development of the early theatre was described by David Russell in The Pursuit of Leisure (in Victorian Bradford, 1982).

Derek Barker, Local Studies Library Volunteer