Bradford is famous for spinning and weaving but textile production was only one of a group of important industries which ‘Worstedopolis’ supported. Since several are now almost forgotten by contemporary citizens I should like to draw attention to those which seem unreasonably neglected, in a series of short articles.

I would be delighted if any reader has ever heard of copperas, let alone that it had once been produced close to the city of Bradford. Copperas is nothing whatever to do with the element copper, but is an old name for ‘green vitriol’ or iron II sulphate heptahydrate. Copperas was used in the manufacture of iron gall ink, leather tanning, and a very early process for the production of sulphuric acid. Copperas, like alum, was also important as a mordant in cloth dyeing processes. For centuries both these chemicals were papal monopolies. The monopoly was eventually broken and in the early post-medieval period the production of alum, on the North Yorkshire coast, and copperas, at several sites round the country, marked the origin of the domestic chemical industry. The industry flourished and the UK became the world’s biggest copperas producer.

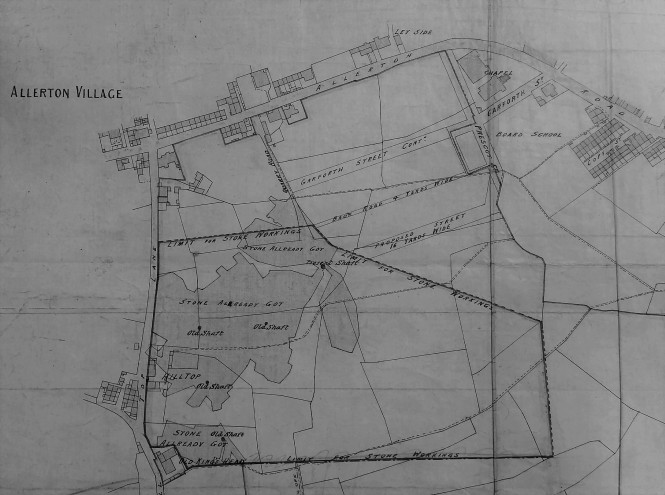

At various times production works existed in several places, this being indicated by name evidence: Copperas Hill in Liverpool, Copperas Road in Colchester, Copperas Point in Chichester Harbour, Copperas House Terrace in Todmorden, and Copperas Bay on the Stour estuary in Essex. The technique adopted was similar at the various sites. Some years ago I was surprised to learn from historian Jean Brown, of the Thornton Antiquarian Society, that Denhome had been a centre of this industry. From trade directory evidence it is clear that, between 1822-1854, copperas was being made at not only there but at Hunslet, Birstall, Huddersfield, Elland, Southowram and Todmoden as well as in the cities of Manchester and Liverpool. Nineteenth century historian William Cudworth, writing about Denholme, recorded that an extensive coal seam was then being worked by Messrs. Townend of Cullingworth and that in parts of this Hard Bed coal ‘quantities of iron pyrites were to be found’. Cudworth stated that the process of converting iron pyrites, or pyrite, into sulphuric acid was carried on along the line of the coal seam’s outcrop. He omitted to say that two copperas works, Field Head and Denholme Gate, were associated with a family called Horsfall.

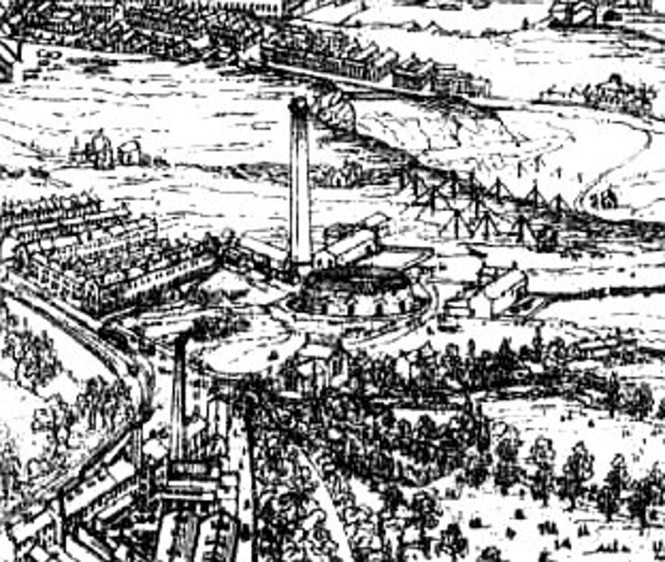

Essentially the Copperas process was the slow oxidation of iron (II) sulphide, obtained as the mineral pyrite, using atmospheric oxygen and rain water to form iron (II) sulphate heptahydrate, that is copperas. Essential to the process was, of course, access to a plentiful supply of pyrite. Pyrite nodules (‘brass lumps’) are found in the Coal Measures in Cumbria and West Yorkshire. At Denholme the producers obtained the nodules and placed them in ‘beds’ lined with clay. They were then left to weather for up to six years. Towards the end of this time they began to produce a large quantity of liquor, a dilute solution of hydrated ferrous sulphate and sulphuric acid, which was pumped into a lead boiler positioned over a furnace. Quantities of additional scrap iron were added to increase the final yield. As the liquor was reduced by evaporation more liquor was added. When it was sufficiently concentrated the liquor was tapped off into a cooling tank. As the solution cooled the copperas crystallised in the tank. Crystals were collected, heated to melting point, and poured into moulds; finally the resulting cakes were packed into barrels for transport.

Why did the industry survive in Denholme? The most important property of copperas for nineteenth century textile manufacturers in Bradford must have been that it ‘saddened’ and ‘fixed’ wool dyes. Because it prevented the colour from washing out or fading, copperas became an essential part of the black dyeing process, especially for woollen cloth in conjunction with log-wood imported from South America. We known that cheap coal and pyrite nodules could be obtained with minimum transport costs and I imagine that once the plant had been set up there were little additional capital costs.

The cheap manufacture of vitriol, in Bradford and elsewhere, by the lead chamber process inevitably killed off the copperas industry. Once you can make sulphuric acid cheaply and in bulk you can make copperas more quickly by reacting the dilute sulphuric acid with scrap iron fragments and evaporating the result. The discovery, by Sir William Henry Perkin in 1856, of aniline dyes which did not require mordants were to make copperas largely redundant in dyeing in any case. Elsewhere copperas works were adapted to produce other industrial chemicals but this did not happen at Denholme in its rather rural location. Nevertheless at one time this community was a small but significant centre of Britain’s chemical industry. By 1888, at the very latest, all production had ceased.

If this topic interests you do read the following paper which includes Jean Brown’s meticulous family history studies:

D.J.Barker & Jean K Brown, Bradford’s Forgotten Industry: Copperas Manufacture in Denholme, Bradford Antiquary, (2015) 3rd series, 19, 25-38.

Derek Barker, Local Studies Library Volunteer.