This article is an extract from The Illustrated History of Bradford’s Suburbs 2002

THE township of Idle, to the north of Bradford, has always been quite large in both area and population. William Cudworth described the extent of Idle in Round About Bradford (1876) as reaching ‘…from Apperley Bridge to Windhill Bridge, and from Buck Mill to Bolton Outlanes’. The population today, due to the new housing developments that rapidly appeared from the mid – 20th century onwards, is near to 10,000.

The origins of the name Idle can be the subject of much speculation. The spelling of the word in historical documents is often Odell or Ydell, and J. Horsfall Turner, the noted Bradford historian, stated that the spelling Idle was frequently used in the Calverley parish register for the best part of 300 years. Another Bradford historian, William Claridge suggested that the village took its name from the fact that much of the locality was uncultivated moorland; land that was literally idle.

Idle is well documented through history, and indeed seems to have been settled, or at least passed through, as far back as Roman times.

One William Storey, when opening a quarry on Idle Moor in around 1800, found many Roman coins, and human remains enclosed in stone were also discovered. Written records mention Idle (or, rather, ldel) as far back as the 12th century, when Nigel de Plumpton is quoted as giving a piece of land there to the nuns of Esholt. The Plumpton Family are associated to quite a considerable extent with ldle’s past, and Sir William Plumpton and his son and heir (also William) took part in the Battle of Towton near Tadcaster in 1461. The younger William was killed in the battle, plunging the Plumptons into years of turmoil and dispute, which eventually saw the Manor of idle being first halved and then quartered, the portions being owned at any one time by George, Earl of Cumberland (father of Lady Anne Clifford), and Sir John Constable, who split his half between his two daughters. Possession of the manor eventually ended up in the hands of Robert Stansfield, of Bradford, who bought it in the 1750’s from the Calverley family. A detailed account of this early period in Idle’s history is available in Cudworth’s Round About Bradford.

By the mid to late 19th century, Idle, like much of the Bradford district, was heavily involved in the textile industry. A look at the Ordnance Survey map of 1893 shows many mills in the area, including Castle Mills, Union Mill on Butt Lane and the nearby New Mills. By the 1870s around 1,100 people from Idle were employed in the township’s mills. Idle seems to have achieved some kind of parity in the size of the mills that operated there. Cudworth states that no giant manufacturer dominated the neighbouring companies in the village. Indeed he goes on to say that the villagers of the late 19th century were probably the most ‘equal’ in the entire land, with no man of exalted rank or great wealth residing in the township. The villagers displayed a prominent love of their home but Cudworth found them rather ‘clannish’ in their attitudes to outsiders.

Another source of income and employment in 19th century Idle was quarrying. Stone was dug underground from beneath Idle Moor and raised to the surface via deep shafts, so unlike areas such as Bradford Moor with its vast coal mining operations, the landscape was not utterly ruined. Idle stone was well known and was considered superior to stone from many other areas. It was used on public buildings in many towns in England, and was even exported as far as China, Australia and South America. Among those involved in extracting Idle stone in the early 19th century were William Storey of nearby Apperley, William Child of Greengates, and later Thomas Denbigh, among others.

Idle grew rapidly during the 19th century, reflecting an increase in the population of the Bradford district as a whole. In 1801 the township’s population had been around 3,400, yet by 1871 it had risen to over 12,000.

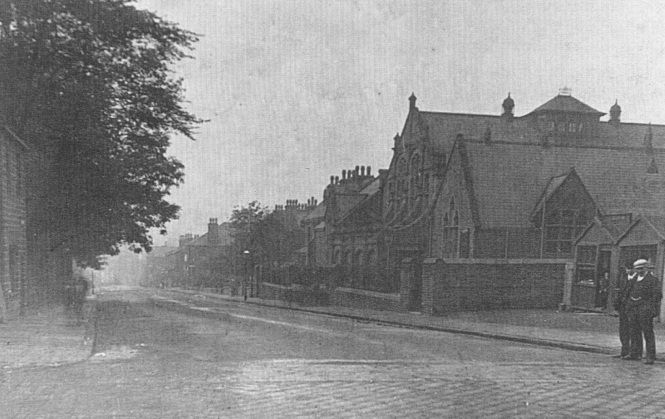

At this time the village itself was well established, along lines that are easily recognisable today. At the top of the village, on Towngate, the Old Chapel of Ease, which was erected in 1630, was still in its original use. The chapel came by its name due to the fact that the nearest parish church was at Calverley, quite a trek away, so the chapel was quite literally built for the ease of the people of Idle. The building currently houses the highly successful Stage 84 drama school. Adjoining the Old Chapel was the township’s lock-up, complete with stocks. On the opposite side of Towngate and a little further down stands Holy Trinity Church, built in 1830. Just across from the church is the former library building, a large Victorian structure which seems to loom over the road.

The rooms above the library were latterly used as meeting rooms for local clubs and societies but were once used for meetings of the Idle local board, which oversaw the township’s affairs. The library moved into former shop premises in a more centralised location just below the Green in the early 1990s.

Idle can aptly be described as a village of two halves. First there is the top half, centred around High Street, which runs steeply downhill from Highfield Road to the Green, from around which the bottom half of Idle radiates. It was at the junction of Highfield Road and High Street that workmen making road improvements uncovered three ancient cellars. The discovery, in 1987, caused much excitement in the local community, and it was suggested that the cellars offered proof of the location of the old Manor House, lost to historians for many years. The proof of this theory may never now be tested as the cellars, which may have had underground passages running to Holy Trinity Church, were subsequently filled in. High Street is also home to the wonderfully named Idle Working Men’s Club. The club has found international fame due to its name and has boasted celebrities such as jockey Lester Piggott and Tom O’Connor among its honorary members.

Idle Working Men’s Club

The bottom half of the village still boasts an array of small local shops, but the lure of nearby supermarkets with their cheap prices has inevitably caused something of a decline. In its heyday Idle had its own railway station and cinema, both now long gone. The station was on the line between Laisterdyke and Windhill, which opened to passengers in April 1875.

Sadly there is now little evidence left of the railway line that neatly bisected the village, reinforcing the division between upper and lower Idle.

Idle today is a busy, well-populated suburb of Bradford. Smart, early 20th century housing lines Highfield Road, and a modern complex of flats stands on Bradford Road, at its junction with ldlecroft Road. The village itself has many excellent facilities for its residents to enjoy. Small shops around the Green almost give the centre of Idle the appearance of a Dales market town. Idle boasts its fair share of pubs – the New Inn and the White Bear at the very top of the village, the Alexander and the Brewery Tap down on Albion Road, and the White Swan, which stands on the Green, to name but a few.

The Green, Idle

The village has two supermarkets within easy reach, and a new medical centre was built on Highfield Road in the early 1990s, and the village has numerous clubs and societies to occupy its residents.

Like many of Bradford’s other suburbs then, Idle is a popular, pleasant place to live, offering all the trappings of modern living, yet retaining something of its historic appearance and charm. This is most definitely one part of Bradford that doesn’t live up to its name.

Further Reading

Cudworth, William. Round About Bradford, 1876. (Reproduced 1968, Arthur Dobson Publishing Co.)

Watson, W. Idlethorp, 1951.

White, E. Idle Folk Idle & Thackley Heritage Group, 1995.

White, E. Idle, an Industrial Village Idle & Thackley Heritage Group, 1992.