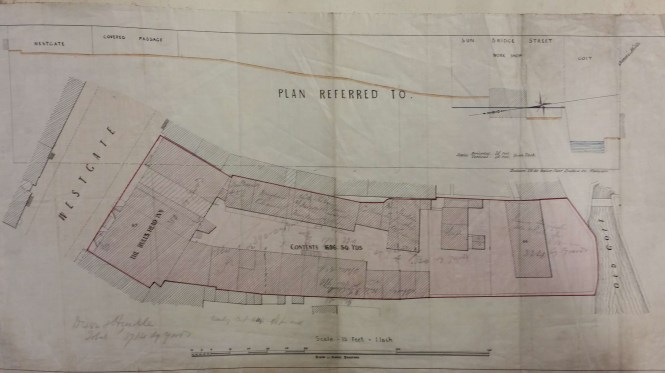

It is relatively unusual to be able to match plans with a surviving drawing. The first image is a map in the Local Studies Library reserve collection which plots a strip of land extending from Westgate, near the city centre, down to the old goit which once supplied the Soke Mill (or Queen’s Mill) with water. Very helpfully it unmistakably identifies a building called the Bull’s Head Inn.

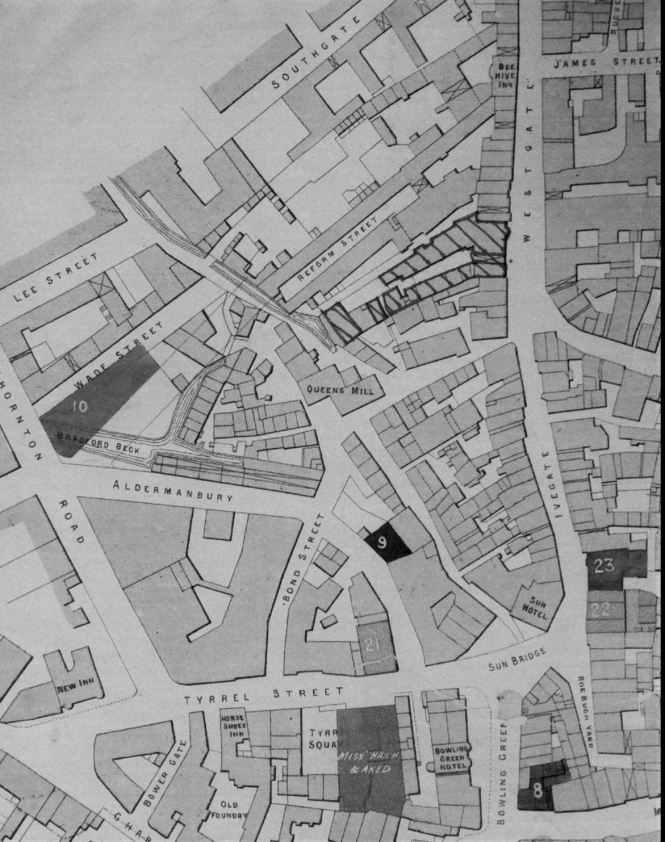

In the second map from the same collection I have hatched the buildings concerned to place them in a more general view of this part of Bradford in the years 1870-80. The creation of new thoroughfares, and extensive building redevelopment, results in a very different street pattern today.

William Scruton, in his Pen & Pencil Pictures of Old Bradford included an illustration of the Bull’s Head itself. In this third image you may just be able to make out the design on the tavern sign. Neither drawing nor plans can be later than 1886 by which time the inn was no longer in existence, but it is likely that they are approximately contemporary. I know that there were other Bull’s Heads in Great Horton, Baildon, Thornton and Halifax and for this reason it is important compare images to check that everything matches up. The prominent features in the drawing are the projecting windows on either side of the door and the arched passageway which gave access to the rear of the property which was known as Bull’s Head Yard. These features are replicated in the plan, so there really can be little doubt that we are looking at a single building.

Scruton says that at one time in front of this inn was a ring for bull-baiting, which presumably provided its name. Close-by was the town pillory in which offenders were manacled while being subject to the abuse of passers-by who could hurl eggs or fruit at them. I have seen a watercolour print which places the pillory on a wooden stage just about where the figure is sitting. This form of punishment was outlawed in 1830 and bull-baiting was forbidden after 1835. The Victorian historian William Cudworth, in his own account of the inn, doesn’t mention ball-baiting but says that in front of it was a market with rows of butchers’ stalls; another possible source for the name then. Whatever the truth there is not much doubt that Scruton was thinking of the situation in the late eighteenth century. At that time the Bull’s Head was used by merchants, manufacturers and woolstaplers. The first Bradford Club was founded there, according to Cudworth, in 1760. By the early nineteenth century a Mrs Duckitt was the host. She was apparently famous for her rum punch, which isn’t a beverage that I have ever tried. An Act of Parliament in 1805 appointed commissioners for levying rates and improving Bradford roads and lighting. These commissioners, a sort of primitive town council, met at the Bull’s Head. In some ways it was our first Town Hall. Apparently 60 years before Scruton’s book was published, which would therefore be in the 1830s, the inn was also a rendezvous for town and country musicians.

Inns are usually easy to trace in other Local Studies resources such as trade directories and newspapers. I only wish I had more time for a more detailed study. The 1818 and 1822 commercial directories place Jeremiah Illingworth in charge at the Bull’s Head. It seems then to have then doubled as an Excise Office. In 1829 Hannah Illingworth, perhaps Jeremiah’s widow, ran the establishment which was clearly a large one since on one occasion in 1834 no less that fifty friends of Airedale College dined there together. On the other hand there are reports of fights in the street outside, and in 1837 a licenced hawker, Henry Stephens by name, was fined the huge sum of £10 for trying to sell a watch and razors in the bar parlour. Later that same year Joseph Sugden, who was now in charge, was reported as providing another excellent dinner, this time for 56 members of the Ancient Order of Oddfellows. Acceptable early Victorian dinners always seem to be described as ‘good’ or ‘excellent’ for some reason.

At the time of the 1850 Ibbetson directory Joseph Sugden was still the host. Manufacturers from outside Bradford would attend an inn on a regular basis so that they could be easily found if you wished to transact business. Among textile men at the Bull’s Head you could find John Anderton, manufacturer of Harden, and Samuel Dawson of Wakefield. Other visitors were Messrs Pilling, corn millers, and John Hirst, land agent, who attended on Thursdays. The LSL offers free access to the family history site Ancestry.UK and using this site it is not hard to find Joseph Sugden (47) in the 1851 Bradford census. He lives with his wife Sarah and two children, together with a charwoman, an ostler, and three servants. I assume he would also have non-resident staff. His immediate neighbours are: booksellers, druggists, drapers and plumbers.

Some of Sugden’s patrons must surely have come from the surrounding streets where wool-combing was a very common occupation. This trade was on the verge of being destroyed by the mechanical wool-combs developed in Bradford by Samuel Cunliffe Lister and Isaac Holden. The habits of those patrons is hinted at by the fact that in 1869 Thomas Burrows was arrested in Bull’s Head Yard in possession of two spittoons, thought to be the property of Thomas Waterhouse, then of the Inn. It remained a significant local building and in 1874 the Bradford Musical Union dined there, inviting the Mayor and local jeweller Manoah Rhodes as guests. I have followed entries for the inn in the Bradford Observer up to 1875, when it was being used for election candidates’ addresses.

The Bull’s Head is on the same alignment as Westgate, as indeed are all neighbouring premises. The rear yards however are aligned as an angle to the thoroughfare. This is also true in the much older 1800 map of Bradford. The yards and properties are running south-west following even earlier field boundaries. You may be able to see that the first map has been annotated in pencil. The annotations are not generally legible but they would appear to indicate the types of premises found in Bull’s Head Yard. The only proprietor I can be certain of is a Mrs Smiddles who ran a tripe shop, but there are also sheds and stables. I haven’t been very successful in tracking down any other businesses based there. In 1850 John Hebden, fishmonger, gave this address but the 1851 census shows he was actually living nearby in Reform Street which is clearly shown in the second map. Perhaps he had a shop in the yard combined with a house entered from the next street. In 1857 Tennand, Hall & Hill of Manchester, who were tanners and curriers, advertised that they visited Bull’s Head Yard weekly.

The Bull’s Head at 11 Westgate was still run by Joseph Sugden according to a 1866 trade directory. It is listed under the name J Halliday in the directory of 1879-80. In the directory of 1883 the inn is missing. The Lord of the Manor had the medieval right to a corn-milling monopoly at the Soke Mill, which had stood above Aldermanbury for centuries. Bradford Corporation bought out this right in 1870. In the mid 1870s clearance of much of the property in this area began, and modern Godwin Street was created. At the top of the first plan the elevation of various points is related to Sun Bridge Road. This would have been relevant during such a period of development. Does any of this area survive? I would imagine that everything was destroyed when Godwin Street was brought up to intersect with Westgate. Walking along Godwin Street and Sackville Street today, both in reality and using Google Earth, I cannot persuade myself that any of the mapped buildings are still present. But I should so very much like to be proved wrong.

Derek Barker, Local Studies Library Volunteer