Bradford is famous for spinning and weaving but textile production was only one of a group of important industries which ‘Worstedopolis’ supported. Since several are now almost forgotten by contemporary citizens I should like to draw attention to those which seem unreasonably neglected, in a series of short articles.

Bradford lies on the northern edge of the great Yorkshire & Nottinghamshire coal field. The solid rocks under the city, called the ‘Coal Measures’, were laid down on top of the Millstone Grit in the Carboniferous geological period around 320 million years ago. In the Carboniferous ‘Bradford’ was near the equator and must have witnessed episodes of luxuriant tropical fern and horsetail growth, together with muddy coastal lagoons, vast debris deposits from a river delta, and occasional incursions of the sea. A little like the Florida Everglades today perhaps. The rocks created in this way resemble a pile of sponge cakes cut in half and consisting of layers of grey mudstone, sandstones, coal and fireclay. All these minerals once had a commercial value. The remains of many living creatures survive in mudstones or sandstones. Cliffe Castle Museum, Keighley has an important collection of such fossils.

If you examine any portion of the first Ordnance Survey map of Bradford, surveyed in the late 1840s, you will see collieries, coal pits and ‘old pits’ scattered everywhere. Coal production was clearly a huge industry and in the 1860s Bradford produced as much of the mineral as Barnsley. In addition to a domestic supply coal was needed for coke manufacture, town gas production, and to power many hundreds of the Borough’s steam engines. It would have fuelled industries such as brick-making and lime-burning which will be examined in future articles. Coal was brought into the town centre and sold from staithes, this being a place adjacent to a highway from which merchants could collect a supply for subsequent delivery to their customers.

This 200 year old map of east Bradford shows the position of two coal staithes. The date is probably around 1825 since Leeds Road is labelled as ‘New Road’.

In this map one staithe is clearly marked J.S. & Co. This must represent John Sturges (or Sturgess) & Co., which was the company that operated Bowling Iron Works. The ‘new rail road’ drawn is in fact a mineral carrying tramway bringing coal in trucks to the Eastbrook staithe, by rope haulage. There is second coal staithe (or stay) at the junction of Well Street and Hall Ings. This is evidently operated by J.J. & Co. who I cannot yet identify. There were staithes adjacent to the canal basin and the bulk transport of coal was very much in the minds of the first canal promoters.

In north Bradford the coal mined was largely from the Hard Bed, Soft Bed and 36-Yard seams which are the deepest in the Coal Measures. As you move up the Aire Valley from Bingley towards Keighley there were a further set of collieries based on even deeper seams of coal in the underlying Millstone Grit series of rocks. Coal mining in north Bradford may have been very extensive, but the coal seams were thin and relatively unproductive. At the better capitalised late 18th and 19th century south Bradford pits mineral tramways took at least 50% of the coal mined to supply fuel for the profitable blast furnaces at Bowling and Low Moor. Here thicker seams, higher in the Coal Measures series, were exploited. Ironstone and coal were removed from the Black Bed and, underneath this, the Better Bed provided coal low in sulphur and phosphorus, ideal for coke fuelled iron smelting. Most old mine workings are now concealed by urban development but even today walks in Heaton or Northcliffe Woods, or on Baildon Moor, will reveal unmistakable evidence of a mining landscape.

One of the many capped colliery shafts on Baildon Moor.

It is likely that the Romans exploited coal in Britain and there were certainly medieval collieries in northern England. I know of good historical evidence for mining in Baildon, Heaton, Shipley, Frizinghall, and Eccleshill in the early 17th century but the Bradford industry is almost certain to have been older, and more widespread. As an example of the evidence there are a series of West Yorkshire Deeds, published in 1931 by the Bradford Historical & Antiquarian Society, and available in the Local Studies Library. One deed reveals that in 1684 Ellen Robinson conveyed her ‘Coles, mynes, seames and quarries of cole’ near a place called Mooreside. Would this be the Moorside, Eccleshill where the Industrial Museum is now situated? Remarkably the rent required of William Rawson, yeoman of Bowling, is ‘one red rose yearly’. Was a ‘rose rent’ effectively a way of giving the beneficiary, a relative perhaps, all the income from a parcel of land while not transferring its title of ownership? The colour of the rose is rather surprising if the parties involved were both from Yorkshire.

The earliest mining described by Bradford historian William Cudworth was a little later in 1699 when about twenty freeholders of Bolton entered into a mutual agreement for ‘getting’ coal in that township. The rights to the coal were generally vested in the landowner but a Lord of the Manor retained rights to coal under common land or ‘wastes’. The most frequent way of reaching coal seams was by means of shafts sunk from the surface. Once a shaft was in place the miners created galleries from which the coal was actually removed, with pillars of mineral being left to support the gallery roof. This technique is often called ‘pillar and stall’ mining with the stall (or bord) being the place in which the miners worked at a coal face. Because of these unmined pillars the ‘take’ of coal from a seam may have been as little as 60%. Traditionally coal was not mined under churches, nor the mine-owner’s house!

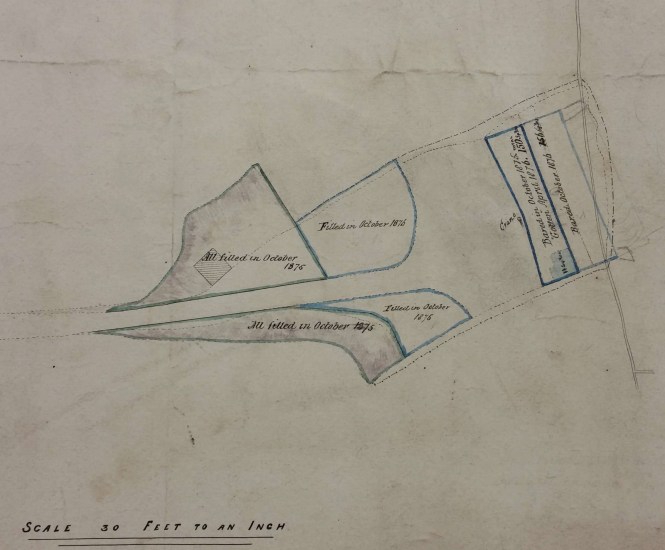

A beautiful colliery plan from the reserve map collection showing pillar & stall mining below Old Allen Common, Wilsden.

As well a shaft to access the galleries a second ventilation shaft was often sunk. When a colliery was working active men were needed as ‘getters’ to hew the coal. If the seams were thin this must have been undertaken in a lying or kneeling position illuminated only by flickering candlelight. Hewed coal was then conveyed in wicker baskets, called corves, by ‘hurriers’ to the shaft bottom from which it could be wound up to the surface by ‘gins’ of various types. Where the topography was favourable seams could also be approached by driving in roughly horizontal tunnels, called inclines, drifts, or ‘day-holes’. Local mining by both methods is well recorded. For Wilsden, for example, there are maps held by both West Yorkshire Archives (Bradford) and the LSL. The Archives have a plan (WYB346 1222 B16) of Old Allen Common in Wilsden including all its collieries. This was ‘made for the purpose of ascertaining the best method of leasing the coal’ by Joseph Fox, surveyor, in 1829. It shows the area where Edward Ferrand, as Lord of the Manor, had mineral rights over common land.

The name ‘bell pit’ is commonly encountered in accounts of early mining. In this method a short shaft was sunk down to a seam and its base was then expanded as the mineral was removed, creating a bell-like profile. When unsafe, because of potential roof collapse, the bell was abandoned and a new shaft sunk nearby. Each bell was filled in turn by waste dug out of its successor. I feel that if shafts were connected underground, or were drained by a passage to the exterior (called an adit or sough), or had some means of providing fresh air for its miners, it seems misleading to call such arrangements ‘bell pits’. ‘Shallow shaft mining’ is perhaps to be preferred which covers all these possibilities.

If you want to explore local coal mining further I would suggest:

J.V. Stephens et al., Geology of the country between Bradford and Skipton, HMSO, 1953. This is essential reading for geological background to any extractive industry.

Richardson, A Geography of Bradford, University of Bradford (1976). This work provides a gentle introduction to mining as it also does to Bradford’s development.

M.C. Gill, Keighley Coal, NMRS, 2004. A most detailed study by an eminent mining authority.

D.J. Barker & T. Woods, Cash from the Coal Measures: the Extractive Industries of Nineteenth Century Shipley. Bradford Antiquary, (2013) 3rd series, 17, 17-36.

Derek Barker, Local Studies Library Volunteer