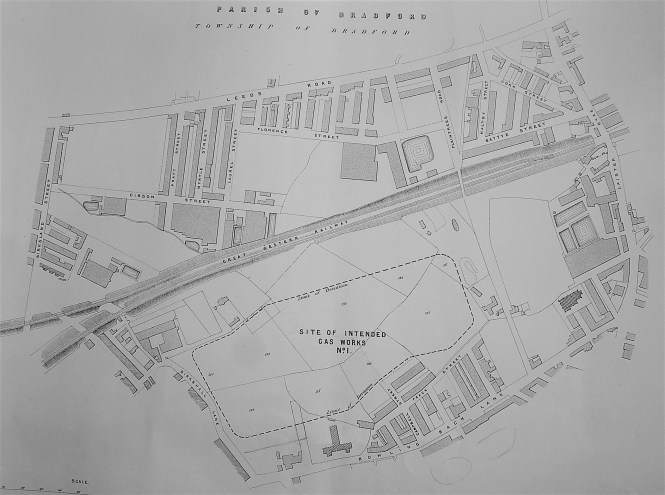

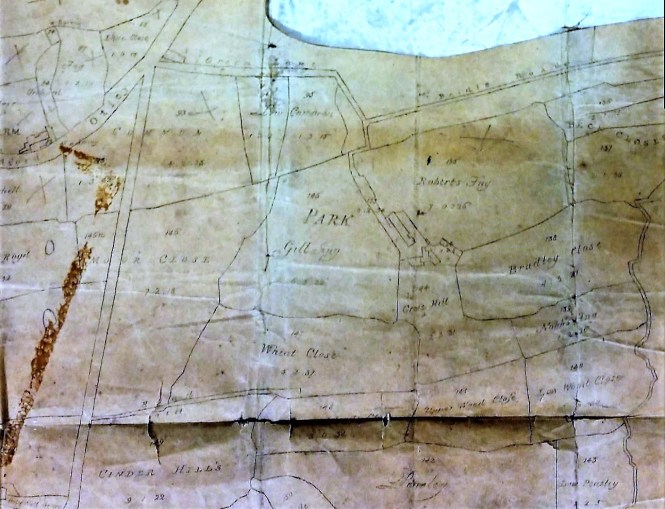

If you are reading this article you probably find maps and plans as interesting as I do. You will certainly understand how easy it is to get distracted, while writing a brief report, by trying to identify all the recorded features and resolve some of the inevitable puzzles. The first image is a detail of a map in the reserve collection which is in poor condition. The parent map is the one produced of the Borough of Bradford in 1873 by Walker & Virr, which is especially valuable since it falls evenly between the two first Ordnance Survey maps of the 1850s and 1890s. The twenty years that preceeded the Walker & Virr map brought huge changes to Horton. In 1850 the community had been surrounded by many coal and ironstone pits, both functioning and disused. Tramways conveyed their products to the Low Moor Ironworks for conversion into best Yorkshire wrought iron. By the 1870s the seams were exhausted, the pits were closed, and there had been considerable housing development.

A map detail showing Great Horton watercourses and main sewers

This map was in a group that evidently came to the Local Studies Library from the city’s Surveyors and Engineers Department. Its purpose is clearly recorded, this being to record Bradford’s main sewerage system and to show storm overflows. The main sewers collected both foul water and surface water. During a rainstorm they could become completely filled. Under those circumstances the plan was for the excess to flow into alternative sewers and ultimately watercourses like the Bradford Beck; not a pretty thought. The positions of the storm overflows are more easily displayed in a second map detail.

A detail from the same map showing sewers in the area between Thornton Road and Legrams Lane

The Borough Surveyor (B.Walker) employed this map. It was clearly being used for at least a decade after its first publication since pencil annotations are dated for the years 1881-83. Having dated the map and identified its use I thought that there were three features of particular interest: the Old Mill, Bracken Hall, and the brick works.

The longer watercourse in the first image is the Horton Beck which provided the water for the Old Mill. A little further down stream, out of sight, was a second corn mill called the New Mill. I assume that the Old Mill started life as a manorial watermill, like Bowling Mill or the Bradford Soke Mill. William Cudworth records that in the nineteenth century the Lord of the Manor of Horton was Sir Watts Horton and then, after his death, his son in law Captain Charles Horton Rhyss. His property came up for sale in 1858 when William Cousen of Cross Lane Mill purchased the lordship. The Old Mill, its farm, and the water rights went to Samuel Dracup a noted textile engineer. He, it appears, eventually converted Old Mill to be a textile mill. I am more interested in an earlier tenant of Old Mill recorded in the Ibbetson’s 1845 Bradford directory, John Beanland. He was the son of Joseph Beanland who was a corn miller and colliery proprietor at Beanland’s Collieries, Fairweather Green. Cudworth says he belonged to a Heaton family. There was certainly a James Beanland (1768-1852), of Firth Carr, Heaton who exploited coal in Frizinghall.

Cudworth describes the impressive looking Bracken Hall as being of a fairly recent origin. I’m sure Cudworth is correct since the Hall is not present on the 1852 OS map of the area. It was inhabited by William Ramsden who was the owner, with his brother John, of Cliffe Mill. This was a Horton worsted mill which can be seen in the centre left of the first map. Bracken Hall was described as being ‘surrounded by a thriving plantation’ which is certainly the appearance that this map records. In the 1881 census William Bracken (54) and his wife Sarah (57) were living at the Hall rather modestly, with only a cook and a housemaid. I am not sure when the house was demolished. It certainly survived into the twentieth century but is missing from the 1930s OS maps. Before the construction of the Hall there were fields and a pre-existing farmhouse which I assume is the small building called Bracken Hill on the OS 1852 map. The land was owned by Mrs Ann Giles who possessed much property in Great Horton including Haycliffe Hill and Southfield Lane with the fields in between. The means by which she acquired her estate was quite complicated. Hannah Gilpin Sharp (1743-1823) of Horton Hall bequeathed her mansion, with all her land in Bradford, to her nephew, Captain Thomas Gilpin and his male heirs, and in ‘default of issue’ to her niece Ann Kitchen. Captain Gilpin, after enjoying the estates for only three years, died at Madeira in the year 1826 without ever having been married. So Ann Kitchen came into the property. In 1828 she married a clerk in Somerset House, as her second husband. Cudworth records him as Edward Giles, but I believe that Edmund is the correct name and the couple were united at St Pancras Old Church. Here their son, another Edmund, was baptised the following year. Ann Giles lived in Tavistock Place but her husband died in 1832 leaving his infant son as heir to the Horton estates. At the age of 25 this son Edmund eventually went to Australia, being enamoured of sea life, but only lived three days after landing in the colony. In 1839 an Act had been passed for disposing of the Giles estate at Horton, owing to the great increase of buildings in the immediate vicinity. Land belonging to ‘Mrs Giles’ are common on maps of Bradford and Horton. In the 1851 census she and Edmund were staying with her daughter by her first marriage, Ann Haines, who was ultimately to inherit her estate.

It seems that I may have fallen at the final hurdle since I cannot identify the owner of the brickworks. In the 1880s Great Horton had no less than three brickworks: Beldon Road, Haycliffe Road and this mapped works in the High Street. The Beldon Road works was owned by the Bradford Brick & Tile Company in the years 1875-1927. The Haycliffe Road works were linked in 1871 with an E.Hopkinson (Wm. Holdsworth manager) and in the years 1875-1883 William Holdsworth seems to be the owner himself. The High Street brick-works was the earliest but its existence may have been brief since it is attested only by maps of 1873 and 1882. It does not feature in the libraries’s stock of Trade Directories. One possibility is that it belonged to Robert Bown ‘coal merchant and brickmaker’ whose bankrupcy was reported in the Bradford Observer in March 1864. Twenty thousand bricks from the ‘Horton yard’ were to be auctioned. A coal merchant of that name lived in Little Horton in the 1861 census. Even if this is true who kept the building going for at least another ten years?

If you would like to learn more about historic Horton I can recommend:

www.bradford.gov.uk/media/2373/greathortonconservationareaassessment.pdf

Derek Barker, Local Studies Library Volunteer.