Recently a map introduced me to another strange unknown fragment of local history. Legal actions seem to be the explanation of several depositions in the Local Studies Library reserve collection, but after the passage of many decades it can be very difficult to establish what such actions were about, or who won, or why anyone ever thought the issues were important enough to spend a small fortune on lawyers’ fees. I am in a slightly better position with the case of Ferrand v Milligan (1845) since I believe I can provide answers to the first two questions at least, and possibly the third.

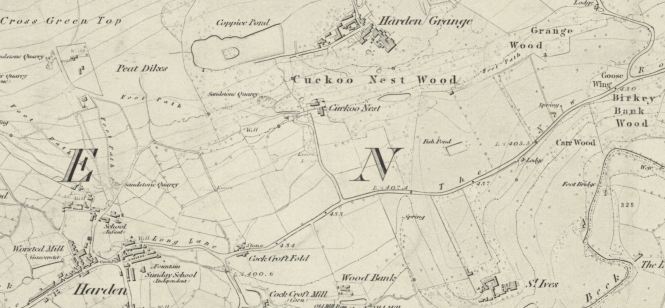

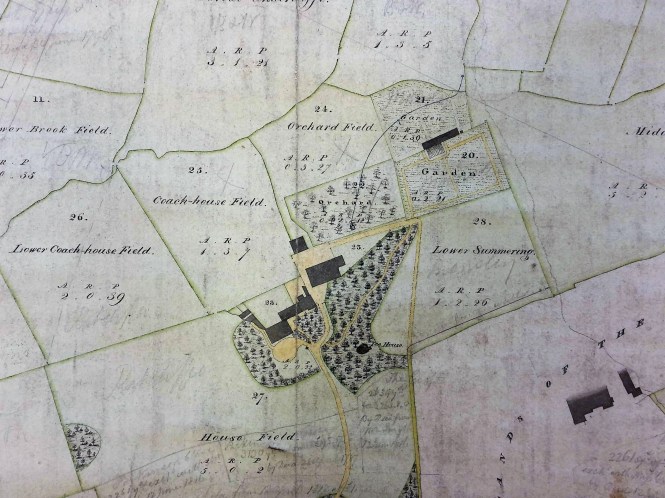

The whole map, of which this is a detail, is additionally marked ‘Plaintiff’s plan No 1’ and so it was evidently once used by Mr Ferrand or his legal team. No railway lines are marked which would suggest a date prior to 1847. In fact it closely resembles the Fox map of the area from 1830 which presumably was redrawn for the purposes of litigation. It is immediately obvious that St Ives is not in its present location. The valuable website of the Friends of St Ives confirms that this house swapped names with Harden Grange a decade or more later, in 1858. The importance of this fact is that the name ‘Harden Grange’ that was used in reports of this case, and which appears on the maps or in my account, was the building we think of today as St Ives. Aside from maps my other researches have been in the pages of contemporary local newspapers.

I am certain that the plaintiff in Ferrand v Milligan was William Busfeild Ferrand (1809-1889), landowner, magistrate, and at this time the Conservative MP for Knaresborough. He lived at Harden Grange and was a friend of Richard Oastler. William’s mother was called Sarah Ferrand. As often happened in the nineteenth century William adopted her surname in 1839 in order to receive a large estate from his maternal uncle. This bequest was ultimately transmitted through his mother when she herself died in 1854. The estate he obtained included both St Ives and Harden Grange, where he was living at the time of the action. The principle defendant is variously named as Mr Milligan or Robert Milligan: who was he? Evidently he must have had at least a modest competence to undertake the expense of litigation and the 1851 census suggests he was Robert Milligan, aged 32, of Harden Mill, worsted spinner. A man of this name had certainly been operating the water and steam powered worsted mill since 1842. There was also a Walter Milligan, aged 57 and born in Scotland, a worsted & alpaca manufacturer of 38 Myrtle Place, Bingley. I think that the two men were probably son and father. Walter Milligan & Son are listed as the proprietors of Harden Mill in many reports until 1861. I should add that Robert Milligan is quite certainly not the contemporary ‘travelling Scotchman’ and Liberal MP of that name who was also Bradford’s first Mayor. This important figure in Bradford’s history had his estate at Rawdon. If Robert Milligan of Harden Mill was indeed the man then he and William Ferrand had been acquainted in happier times. From 1842 there is a pleasant story concerning the properties of both men being visited by children from a Wesleyan Sunday School outing.

William Busfeild Ferrand does not always seem to have been popular with the editors of local newspapers. This should be taken into consideration when reading the initial account of events, published by The Bradford Observer and Halifax, Huddersfield, and Keighley Reporter under the title of ‘a village in uproar’, on 18 May 1843. It describes how a certain James Bower walked, with a terrier dog at his heels, along a road through Harden Grange Fold. There he was allegedly seized by Mr Ferrand and his servants while the terrier was ‘worried to death’ by their dogs. I’m relieved to say that, despite the title I’ve adopted, the poor terrier shed the only blood spilled in these events. Because of local indignation the whole episode was reported to Mr R Milligan, who was then Surveyor of the Highways, and he it was who insisted on the right of the public to use the road concerned.

After that things got rapidly out of hand. Robert Milligan proceeded to break down the gate that led on to the road, and to walk ostentatiously down it with a crowd looking on. Mr Ferrand, it was said, hired men to guard what he evidently considered to be his own property. If necessary his rights were to be protected ‘by force’. An emergency meeting of the ratepayers of Harden was summoned and held in Bingley churchyard. Mr Milligan’s conduct was cordially approved by the gathering. Mr Holden of Cullingworth (the future Sir Isaac Holden but then merely the manager of Townend’s Worsted Mill) proposed a motion empowering Milligan ‘to take such steps in law as may be found necessary for defending the right of the public to use the said road’. An attempt by Mr Middlebrook, a recent Highway Surveyor and friend of William Ferrand, to put any expenses involved squarely on the shoulders of Milligan, rather than the ratepayers, was defeated. The newspaper report was very partisan to the inhabitants of Harden who were praised for resisting ‘oppressive encroachments’.

The inevitable legal case was heard at York Spring Assizes in March 1844 before Judge Coltman; bizarrely William Ferrand JP MP had already been sworn in as a member of the Grand Jury for these assizes. It is clear from reports that the action was for trespass against Milligan, and others, in order to try whether the road which went through the grounds of Harden Grange was indeed a public highway or not. Mr Baines represented the defendants and examined no fewer than 31 witnesses! Mr Knowles for the plaintiff admitted that some local residents and their carts were accustomed to use the road, which ran through a considerable portion of the Harden Grange estate, but he disputed that they had a ‘right’ so to do. He explained that the road had been created in Major Ferrand’s time (c.1797) when he was a tenant, and also that William Ferrand was not actually the owner of Harden Grange but ‘entail expectant on his mother’s death’. He further stated his belief that Mr Milligan was animated in his actions by some private feeling, and finally he demanded in excess of 40 shillings damages. The unfortunate jury were then locked away from 7.00 pm until 4.00 am the following morning! With nice judgment they found that there was indeed ‘no carriage road or public foot road’ in existence, but rather than £2 or more the plaintiff (William Ferrand that is) was awarded only the derisory sum of one farthing in damages.

This was not quite the end of the matter. In another bizarre twist there was an associated criminal case, against Milligan and his servants, which saw him hauled up for ‘riot and assault’. The plaintiff and his barrister seem to have understood that Milligan honestly believed he had a right of way past Harden Grange. Mr Ferrand stated that he wished to live in ‘peace and goodwill with his neighbours’ and as a result offered no evidence against him: consequently the prosecution failed. Rather ominously Mr Milligan said that ‘nothing had occurred yet that had shown him that he was mistaken’ and so unsurprisingly, a year later, he tried to renew the action. The legal point at issue was under what circumstances the road had been repaired in Major Ferrand’s day and whether repair was at his own expense, or that of the parish. There was also some doubt over whether this evidence was really admissible: a rather a complicated point for a non-lawyer like me to follow. In any event a further action was not allowed by the court. That didn’t restrain the Bradford & Wakefield Observer who reported that ‘in this weather’ it was dangerous to cross the path of William Ferrand on the moors about Harden Grange.

The original map identified in red the trackway which, I assume, the defendant was using without permission. This extended west from the ‘Lodge’ towards Harden Grange and Cuckoo Nest. It is interesting to note that the Fox 1830 map of the roads between Bingley and Keighley also shows the thoroughfare at issue.

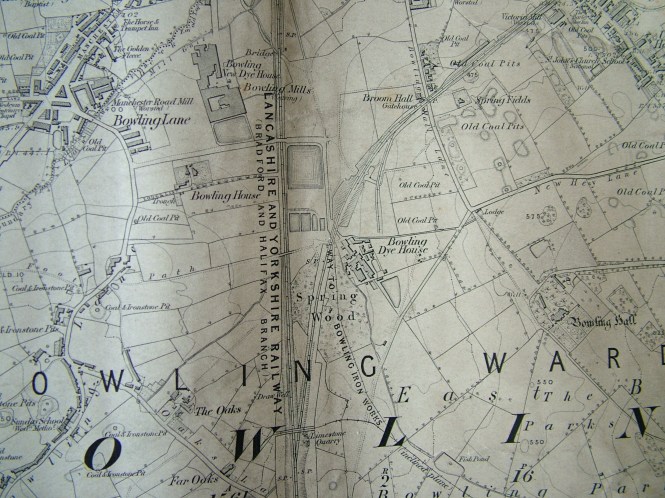

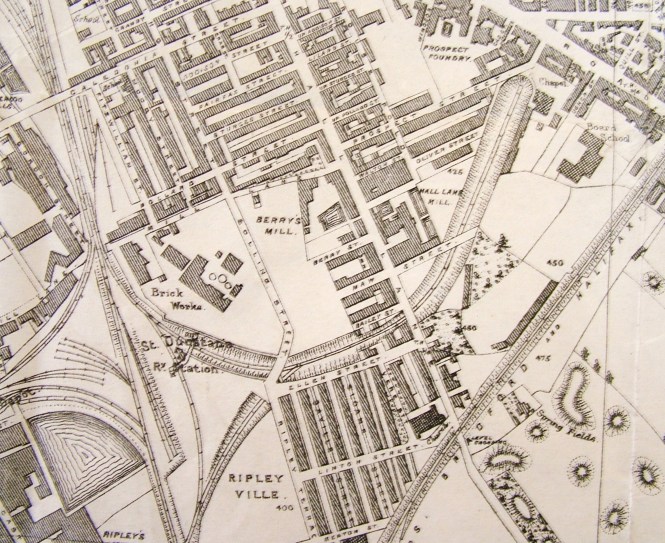

Finally the first OS map of the area which was surveyed around 1847, after the action and the same year that William Ferrand lost his Knaresborough seat, does not mark the trackway as a private road but scarcely shows it at all. The triumph of local landed interest over geography perhaps?

Derek Barker, Local Studies Library Volunteer