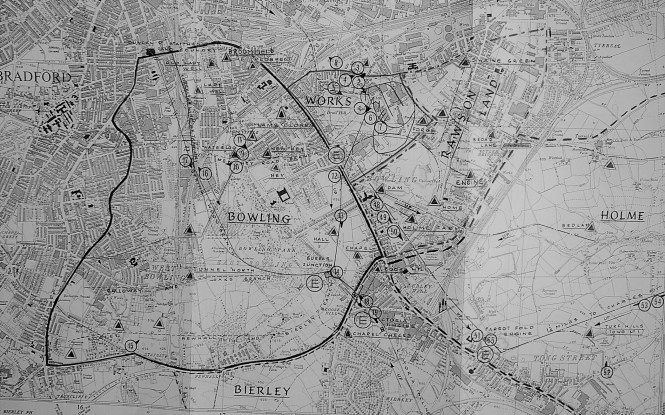

As a family we were what would be called these days “upwardly mobile” and our move from Thornbury to Eccleshill was a modest first step up the social scale:

When I was about eight, we moved to our new home in a sunnier, less tightly packed part of Bradford where we were more likely to play in each other’s gardens than on the local wasteland and back streets as we did at our previous address. It soon became apparent, however, that there were several forbidden places of excitement close by and I began to explore them eagerly with my new friends.

One of my early adventures involved being in a group of boys that climbed up a nearby fire escape running down the side of a local mill:

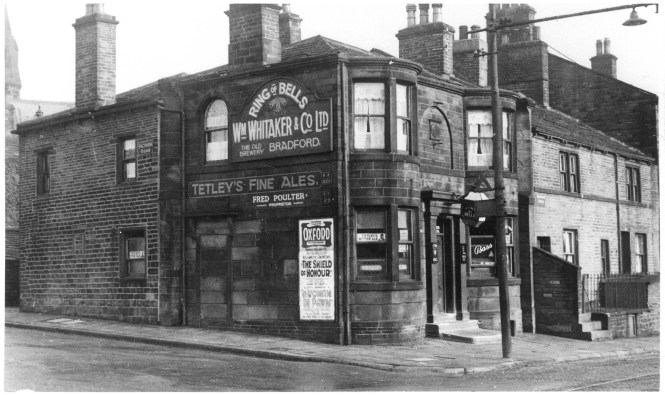

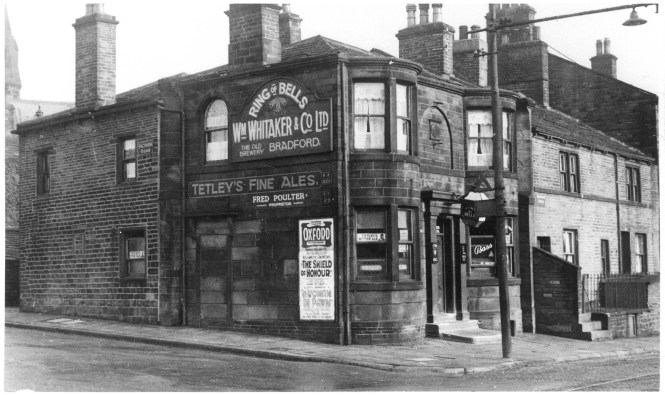

We set foot on this first metal rung and began to climb. The first few steps were easy but, as you could see straight down to the ground through the open mesh of the steps and, as the railings were also quite open and apparently fragile, the climb became more challenging with every step upwards as the ground below grew increasingly distant. We got about two thirds of the way up and were just beginning to appreciate the view over the nearby roofs and chimneys when we noticed the whole structure began to wobble. We stopped and discussed the issue, but decided to carry on and see if we could make out the roof of the Ring O’ Bells pub from the top. Then we heard a voice from way below:

‘Oi! What do you think you’re doing? Get down here now!’

Our lives became less parochial after my father bought a car:

It was about this time we started to travel out to the Dales and other parts of Yorkshire almost every weekend in our second hand black Morris Eight saloon. It was very small, but it had real leather seats and a curtain to pull down over the rear window. Mum and dad sat at the front and Pauline and I sat in the back.

I think the windscreen wipers may have been hand operated and it had to be started with a crank handle. It had black painted wire wheels and chrome plated round hubcaps with a large ‘M’ pressed into them. We all absolutely loved it. The registration plate announced we were DNW613, but we, like so many other aspiring lower middle class families of the time, gave her our own name. We decided, for reasons that now completely escape me, to call her ‘Flossie’. It was my father’s pride and joy and we were all required to put on our best clothes to take a trip in her. My mother would wear her grey suit and my father his grey flannels and the green Harris Tweed jacket with leather buttons and elbow pads that he kept for weekends. The car had two doors, narrow running boards and a spare wheel attached at the back over the small boot. My father often smoked his pipe when driving, which, combined with the smell of waxy shoe polish from my shoes, made me feel quite sick. He had special leather driving gloves with string backs and he almost always wore his flat cap. There was no radio and no heating.

Our journeys and holidays at that time still provide me with many of my better memories:

I still miss the grass, the moors, the large skies, the limestone, the becks and brown rivers, the hills, the cry of the curlew, the bleat of the lambs, the waterfalls, the wild places, and the villages of the Dales. When I was a child I saw in Grassington a farrier shoe a carthorse and, in Reeth, a wheelwright put together an entire cartwheel, hub, spokes, metal tyre and all. I saw farmers cutting wheat with simple farm machinery and making stooks from the sheaves in the fields.

If it rained all day, we drank coffee in the car from my mother’s flask and nibbled ginger biscuits; if it was warm and sunny my sister and I would scramble up the sides of the nearest hill and look down on the tiny figures of our parents sitting by the car in their little picnic chairs, reading the paper or drinking tea. We collected stones, twigs, sheep’s wool, broken birds’ eggs, and cast-off feathers. We picked bilberries by my father’s hatful and took them home for my mother to bake in a pie. It was all very simple, very innocent, and we loved it.

I expect all of us of a certain age remember the year of the coronation:

We had been in our new house perhaps a year when preparations for the queen’s coronation began. It was a more innocent age and everybody seemed keen to participate in the occasion as well as be an onlooker. I can’t remember much deviation from our normal lessons at school, but at home there was quite a lot of excitement and activity. All the residents did something to decorate their house. In our case, where others in the street were satisfied with bunting, my father erected in the centre of the front garden a white flagpole planted firmly in the lawn and supported by guy ropes attached to huge metal tent pegs. It reached beyond the top of the roof. For the week before the coronation, he ran the union flag up the pole every morning before leaving for work and took it down again in the early evening. At each event anybody in close proximity was expected to line up to attention on the path by the side of it (there were usually half a dozen kids, or so, and a sprinkling of adults) and salute whilst singing the national anthem at the same time. I think we may have had a special ceremony during the day when the news of the conquest of Mount Everest came through immediately before the big day on 2nd June 1953. There was not the faintest hint of irony in any of this.

When the Queen came to Bradford some time after her coronation, dozens of us went to see her as she was driven down Pullen Avenue to the roundabout by The Ring O’Bells and on into the Harrogate Road and beyond.

The Queen’s car slowed to less than walking pace as it came close. There was a soft light within the car that caught the glimmer of her youth, the richness of her dress and the brightness of her jewels. She looked utterly beautiful; she was like a film star; glamorous and self-confident, important and revered. She passed slowly, smiling and waving, then, towards the tail end of the crowd, the chauffer kicked onto the accelerator and she was silently swept away at speed into the vastness of the Yorkshire night.

Last time I wrote about a few memories I didn’t put in my memoir and I said I’d try to think of a few more.

Does anybody remember when Leeds, Bradford Airport was simply called Yeadon Aerodrome? I remember watching De Havilland Dragon Rapides take off and land from there many times.

Perhaps you were there at the air display my family and I attended when a jet flew very low along the whole length of the runway at the same time as breaking the sound barrier, crowds of spectators being only yards away either side of it!! How’s that for Health and Safety!! I can still recreate the resulting BANG inside my head!! The jet later climbed almost vertically into the sky and disappeared into the clouds. This makes me think it was probably a prototype English Electric Lightning, but I can’t be sure.

Another memory is of walking one summer evening with my father and looking over the top of a high wall into the premises of the Jowett Motor Car Works.

I think they may already have been experiencing difficulties because my father said something about it and I could also see for myself nothing but rows and rows of (presumably) unsold Javelins and Jupiters filling the whole of the car park outside their factory.

Do you remember the Jowett Javelin, often referred to as the doctor’s car as it was steady and reliable and slightly upmarket? I saw quite a few out and about in Bradford when I lived there.

Next time I’ll tell you about my junior school and the teacher who prepared me for the 11+.

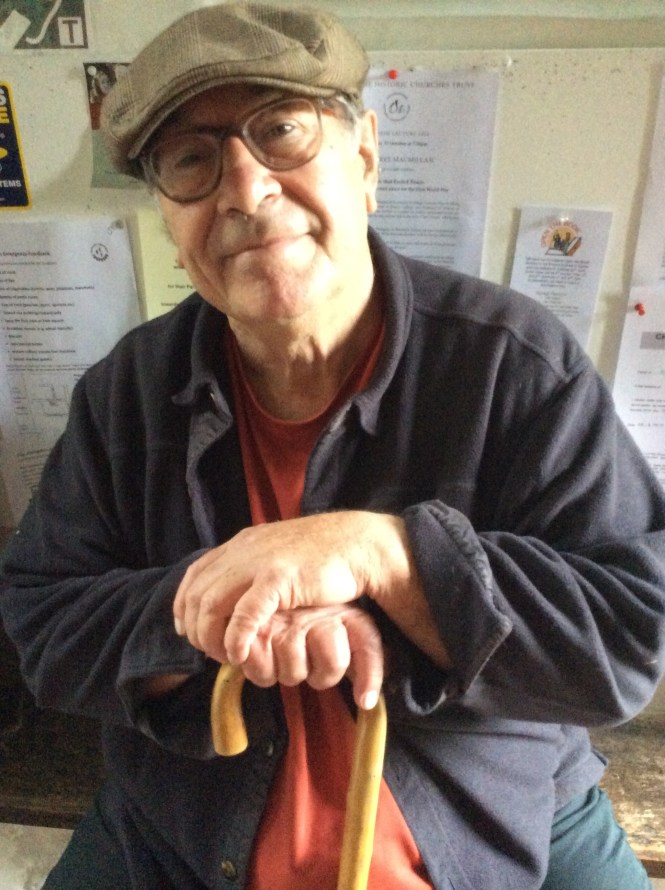

Bob Nichol