Bradford is famous for spinning and weaving but textile production was only one of a group of important industries which ‘Worstedopolis’ supported. Since several are now almost forgotten by contemporary citizens I should like to draw attention to those which seem unreasonably neglected, in a series of short articles.

Together bricks, tiles and terracotta form the ‘ceramic building materials’. This technology was introduced into Britain twice; firstly by the Romans and secondly from the Low Countries in the Middle Ages. The ruined Augustinian priory of St Botolph, Colchester (1100-1150) is a Norman building built of flint rubble and recycled Roman brick. Brick use was insignificant until the fifteenth or early sixteenth centuries when magnificent work appeared at Tattersall Castle, Lincs (1440-1450), Framlingham Castle, Suffolk (soon after 1476), and Hampton Court (1515). The first West Yorkshire brick building is believed to be Temple Newsam House, Leeds (1640-60s). The earliest Bradford brick-maker I have been told about features in the Eccleshill parish records of 1714. Later, in 1718, John Stanhope of Eccleshill wanted to build a new hall and so reached an agreement with John Brown of Nottingham who promised to ‘dig and throw sufficient clay to make 100,000 good stock bricks’. The bricks were large by modern standards, being 10 inches long, 5 inches broad, and 2.5 inches thick when burned.

Hand-moulded bricks were formed by a maker throwing a clay and water mix, of the correct plasticity, into a wooden mould. A skilled maker with a lad could produce a thousand or more bricks daily. Newly moulded green bricks were dried slowly in a hack, or shelter, and could then be successfully fired in a free-standing heap or clamp. Constructing a true kiln needed more expenditure but the firing was more controllable, resulting in a better product and fewer waste bricks. Hand-made bricks survived the spread of the latter mechanical brick presses since their manufacture required little capital. Such bricks are still available today for conservation projects.

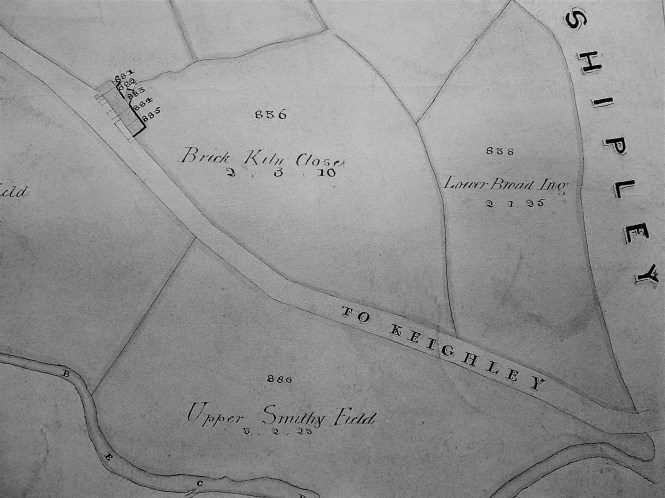

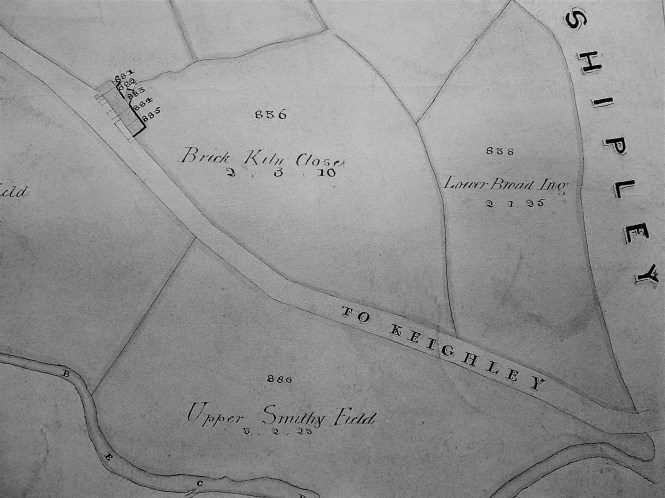

Brick-kiln close, Frizinghall. Field names with brick related elements, or buildings known as Red Hall or House, are common indicators of early brick production and use.

Local historian Tony Woods has studied the Rosse Archive records now in Ireland. He can demonstrate that Heaton coal pits were supplying a brick kiln as long ago as 1776. The field name recorded on the above map from the Local Studies Library collection confirms that there was one such kiln quite close to Heaton village, but there may have been others. A study of early Bradford maps suggests that brick fields preceded established brick works. Evidence from elsewhere suggests that the alluvial clay in such fields was leased by owners to itinerant brick-makers who dug it and prepared it for firing into hand-moulded unmarked, or plain, bricks. There is evidence that there were such undertakings at: Fagley Lane, Bowling Back Lane, Low Moor, Frizinghall, Manningham, Leeds Road, Manchester Road, Bolton, Undercliffe, Shipley, Eccleshill and Wilsden.

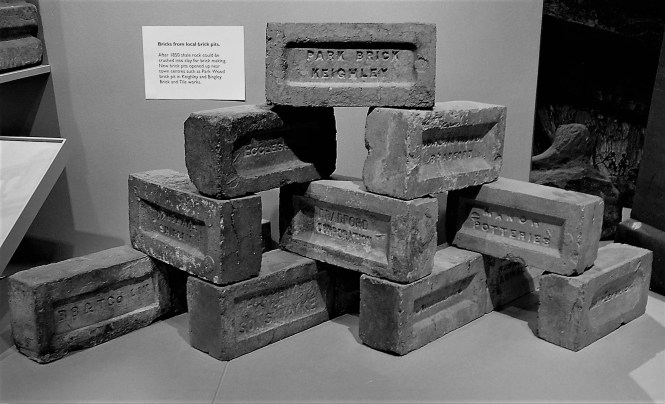

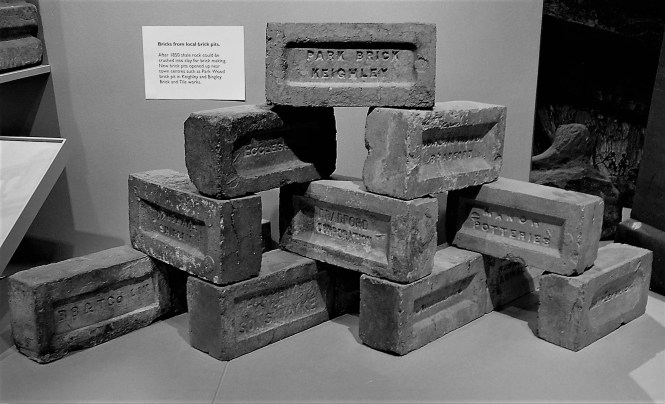

Machine pressed bricks on display at Cliffe Castle Museum, Keighley. Note the [BB&T Co Lim] marked brick at the bottom left.

By the mid-nineteenth century engineers were experimenting with ways of forming bricks mechanically. Common household bricks produced by machine pressing started to appear after 1860, and by the last decades of the century mechanical presses came to dominate production. There were small hand-operated brick presses and large steam powered machines of various patterns. Their use avoided the need to employ skilled brick-makers at a time when the demand for bricks was rapidly increasing. The new machines also produced a uniform product much loved by Victorian architects. In the Bradford area mudstones from the Coal Measures were quarried or mined, and then ground up, to supply the brick presses. The coal seams themselves provided the fuel for firing the bricks. Machine pressed bricks frequently have a depression, or frog, for receiving mortar and may be marked with the manufacturer’s name or initials. Such marks could be stamped into the brick but alternatively brass or iron plates were inserted into the brick moulds. The heads of screws that held these plates in place may also be visible in the fired brick. The interest of those of us involved with bricks was often first captured by finding a marked brick and speculating about its origin.

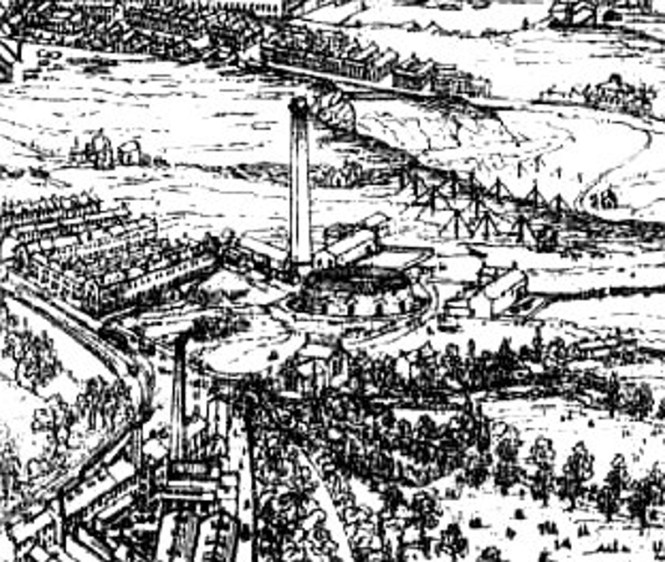

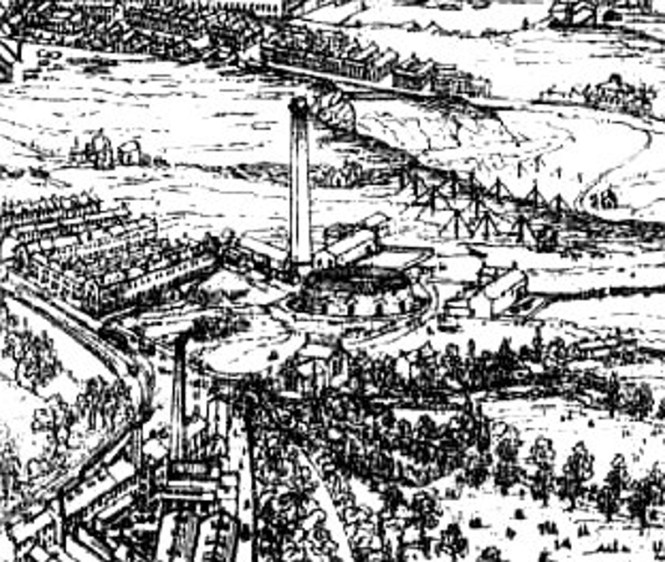

A detail from the drawing accompanying William Cudworth’s Worstedopolis. In the centre is the Hoffman kiln at Daniel Riddiough’s Airedale Road brick works.

New patterns of kiln were adopted. Circular Beehive kilns were popular for single firings. Circular or oval Hoffman kilns were kept continuously alight. Kiln gases, on their way to the chimney, were used to dry green bricks. Hoffman kilns were very economical of fuel but needed a skilled workforce. The Bradford 1856 directory records several local manufacturers: James Fairbank, an important coal merchant and brick maker, was established at the Brick Lane colliery and was ‘sinking for coal’ near the bottom of Whetley Lane. Edward Gittins had arrived from Leicester and was advertising his new patent-brick works at the junction of Wakefield Road and New Hey Road. George Stelling Hogg had come from Leeds and had established the first of his three brick making enterprises in Shipley. George Heaton had leased land from the Earl of Rosse to dig coal and make bricks at the Shipley end of Heaton Woods. As late as the 1881 census I can only identify 204 people in the Bradford area who gave a brick related occupation to the enumerators. This number is dwarfed by coal and ironstone miners, quarrymen, and textile workers.

Research suggests that at one time or another Bradford, Shipley, Bingley and Keighley had more than 60 brick production centres, not of course all working simultaneously, together with additional imports from Halifax, Leeds and Wakefield. At first bricks were used close to the site of manufacture to minimise transport costs. Consequently the few wholly brick houses in Bradford older than a century are likely to be constructed of locally made material. Most readers will be familiar with Bradford’s stone buildings and will naturally ask the question ‘where have all the bricks gone?’ Flues from domestic fires were normally constructed of them, and many Victorian stone buildings will have an inner skin of cheaper brick with stone facings on the visible areas. When you consider the use of bricks employed for Lancashire pattern factory chimneys, or for railway bridge or tunnel linings, the number of producers does not seem excessive. In the long run the railway spelled the end for local suppliers in favour of larger, cheaper, brick producers in Peterborough or Staffordshire.

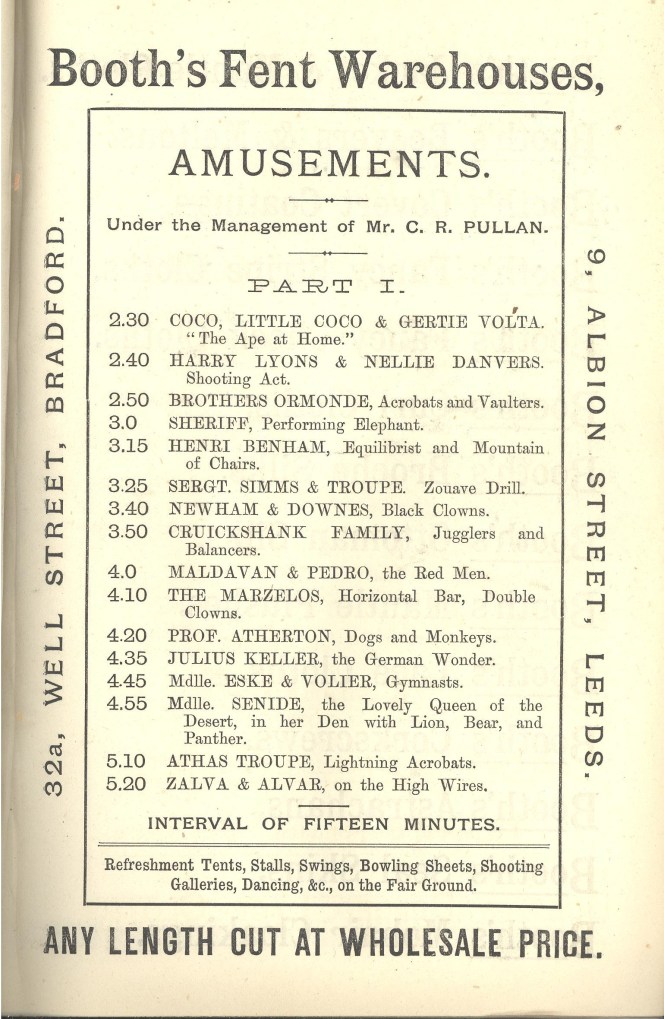

Trade directories are a useful source of information about the brick industry. Advertisements were common.

A popular local house-brick was produced by the Bradford Brick & Tile Company and its most common mark is [BB&T Co Lim]. This company was incorporated in January 1868. The first directors were Halifax businessmen, with the exception of Israel Thornton of East Parade, Bradford (a contractor with his fingers in many pies). At various times it operated a number of kilns: Wapping Road, Whetley Lane and Beldon Rd, Great Horton. By 1901 the Bradford Brick and Tile Company address was simply Knowsley Street, Leeds Road which seems to have been its final enterprise.

If you want to explore brick-making further I would suggest:

D J Barker, Bradford Brick-making: the mud, the men and the mysteries, Bradford Antiquary, (2010) 3rd series 14, 66-77.

The West Yorkshire Archives (Bradford) have more information on the Bradford Brick & Tile Company (10D76/3/113 Box 5). The Local Studies Library collection of trade directories are also an important source of information.

Derek Barker, Local Studies Library Volunteer