Bradford is famous for spinning and weaving but textile production was only one of a group of important industries which ‘Worstedopolis’ supported. Since several are now almost forgotten by contemporary citizens I should like to draw attention to those which seem unreasonably neglected in a series of short articles.

It is the extent, rather than the existence, of Bradford’s stone quarrying industry that has tended to pass out of memory. Bradford sits on a series of Carboniferous period sedimentary rocks called the Lower Coal Measures. This series contains strata of commercially valuable fine grained sandstone such as the well-known Elland Flags. Beneath the Coal Measures is the Millstone Grit series which also provided building stone. Saltaire, for example, is constructed of gritstone. There is no essential difference between these two series of rocks, no unconformity as geologists would put it, and their junction is defined by a particular fossil species. Millstone Grit outcrops to the west and north of the city, forming the scenery of Shipley Glen and Ilkley Moor. The Aire Valley glacier once carved its way deeply into the Millstone Grit making it possible for this rock also to be exploited quite near Bradford. Sandstones and gritstones are largely composed of cemented grains of the hard mineral quartz. Ultimately these grains were derived from weathering igneous rocks and transported here, and deposited, by a vast river delta more than 300 million years ago.

Although stone was principally a construction material it did have other uses, dressed gritstone was once employed for the millstones in corn mills for example. Midgeley Wood at Baildon Green is said to show evidence of this industry, and I should be grateful if any reader could confirm this. Stone could also be crushed for gravel and sand. Any stone occurring in thick beds, which can be cut freely in any direction, is called freestone. Once hewn for facing it is known as ashlar. Gritstone and ragstone are sandstones with coarse, angular, grains that cut with a ragged fracture. Flagstones are thin bedded sandstones ideal for flooring and roofing. When this material is used on a roof it is often referred to as ‘stone slate’ although it is not true slate which is a metamorphic rock. There are plenty of true slate roofs in Bradford of course but slate came by rail, after the mid-nineteenth century, from Wales or, to a lesser extent, the Lake District. The colour of sandstone reflects its iron content. Local stone was often grey when first quarried but it oxidises, on exposure to air, producing a beautiful honey colour. Old quarries are a significant landscape feature in many parts of the Bradford area, and are commonly seen in tithe maps and the first OS maps. Many were subsequently used for land fill, recreational space, or development.

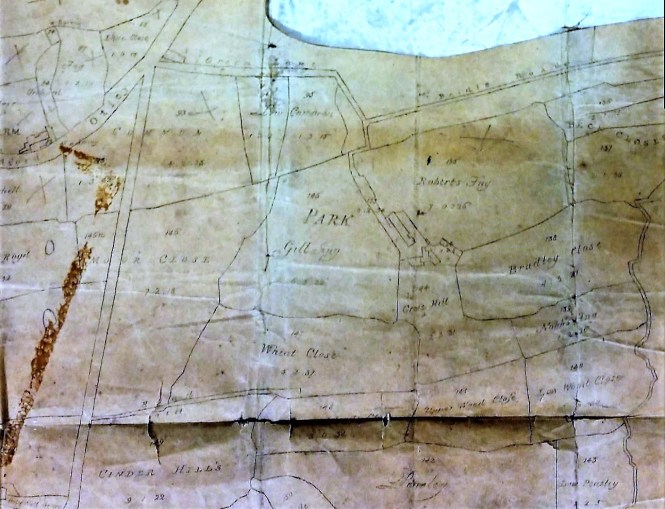

Quarries on Idle Moor in a detail from the first OS map of the area

(surveyed in late 1840s)

In the Middle Ages stone building was confined to high status structures: castles, churches, bridges, and great houses. The only medieval stone buildings now standing in Bradford would seem to be the tower of Bolling Hall and the Cathedral. There must have been a medieval stone quarry in Bradford since the recent Sunbridge Wells development exposed several prison cells, the rear walls of which are portions of a quarry face. Medieval vernacular architecture was in timber, thatch, wattle and daub. The construction of a large timber-framed house required carpentry of a very high order so I cannot think of timber construction as a second best to masonry. After the medieval period there was a ‘great rebuilding’ in brick and stone which in northern Britain occurred quite late, from the mid-seventeenth to early eighteenth century. Was this simply fashion, or an appreciation of the damage fire could do to a wooden urban area? As with many innovations the wealthy were the first to adopt the change. Paper Hall in Bradford is an early example in the city, and East Riddlesden Hall is a seventeenth century millstone grit construction. By the time of the 1800 Bradford map no quarries are marked and the industry has evidently moved to the surrounding high ground.

Since Bradford is famous for its stone buildings it is reasonable to ask how such large quantities were obtained. In some areas, York being an excellent example, cut stone could be recycled from Roman buildings or dissolved abbeys (after the 1540s), but not here. Before the creation of quarries there must have been large quantities of surface stone available which had been originally transported by glacial ice. In an area I know well, Northcliffe Wood in Shipley, large glacial erratic millstone grit boulders are still on the surface, and there are also several large, shallow, surface depressions interpreted as sites from which suitable stone was simply levered up. Stone that was not of sufficient quality for masonry could still be used in drystone walls of which there were vast numbers. It appears that the old quarrymen believed that the presence of a fossil weakened the stone. Rocks containing fossils were not used for ashlar but tended to end up with the wall stone. On some common land, or wastes, local people may have had the right to remove (but not necessarily sell) such surface stone deposits. True quarrying is thought to have begun locally in the seventeenth century and continued until the twentieth. Small quarries would have had a single face for stone extraction; later and larger enterprises had a staggered series of faces, known as ‘bench working’.

A stone quarry illustrated in a detail of the drawing of Bradford which accompanied William Cudworth’s ‘Worstedopolis’ (top right)

The image shows a nineteenth century quarry. Its edge, and the simple derricks used for lifting stone, are easily visible. In the centre is a brick works, a subject to which we will soon return. Many West Yorkshire stones have locality or descriptive names. Bradford quarries accessed Rough Rock (Baildon & Shipley), Stanningley Rock (Northcliffe), Gaisby Rock (Bolton Woods & Spinkwell), and Elland Flags (Thornton, Heaton, Chellow, and Idle). Quarries or delphs could also be dug for special projects like the creation of canals or reservoir dams. There is a small quarry next to the canal at Hirst Wood, Shipley that presumably had this function. At first stone was used near to the site of extraction to minimise transport costs, so most stone houses older than about 150 years will be constructed of very local material. As transport improved there were significant exports. Elland Flags were once widely used for paving slabs in London. Wakefield and Manchester Town Halls were constructed of stone from Spinkwell Quarry, which the architects believed would resist air pollution well. How extensive was the industry? In 1875 William Cudworth knew of 36 stone quarries in Allerton alone, and a further 17 on Rosse land in Shipley and Heaton. Heaton still has its Quarry Hill, Quarry Street and, until recently, The Delvers public house.

Stone-working tools from the permanent collection of

Cliffe Castle Museum, Keighley

Quarry work was skilled and dangerous. Dimension stone was split away from the quarry edge with hammers, chisels and wedges. It would be roughly dressed on the quarry floor. With luck the quarry operator would equip his site with cranes or a tramway to carry the stone on to an adjacent working area. If not strong men would carry stone up a ramp on their backs, supported by two workmates, health and safety regulations being a relatively new development. Newly quarried sandstone is soft and, even before the introduction of steam power, could be cut with saws using sand as an abrasive and water as a coolant. Unusually in this area very valuable stone deposits were sometimes mined as well as quarried.

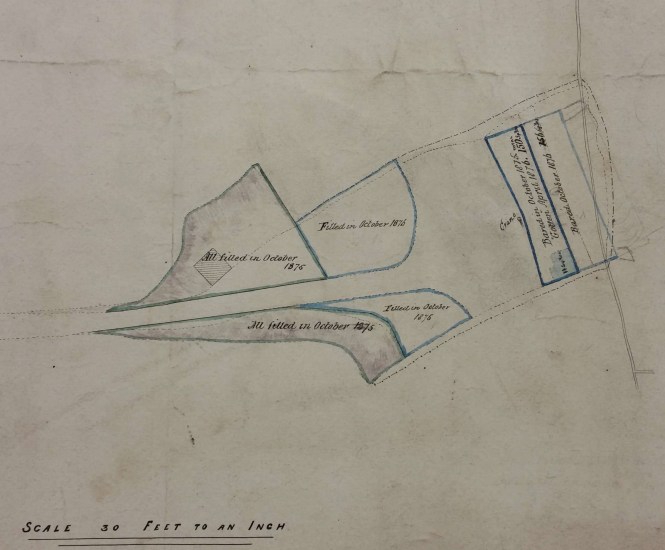

Plan of a stone extraction site in Allerton showing working and ‘old’ shafts

If you want to explore local industries further the gallery devoted to these at Cliffe Castle Museum is an excellent place to begin. For further reading about quarrying I would suggest:

J.V. Stephens et al., Geology of the country between Bradford and Skipton, HMSO, 1953. This is essential reading for geological background to any extractive industry.

David Johnson, Quarrying in the Yorkshire Pennines: an illustrated history, Amberley Publishing, 2016. Bradford is mentioned several times in this comprehensive, engaging, and beautifully illustrated book.

A most informative atlas of West & South Yorkshire Building Stones can be downloaded from the site of the British Geological Survey:

https://www.bgs.ac.uk/downloads/start.cfm?id=2509

Derek Barker, Local Studies Library Volunteer