Bradford is famous for spinning and weaving but textile production was only one of a group of important industries which ‘Worstedopolis’ supported. Since several are now almost forgotten by contemporary citizens I should like to draw attention to those which seem unreasonably neglected, in a series of short articles.

The production of copperas (iron sulphate) and glass in the Bradford area have been completely forgotten. Brick-making has escaped serious study until quite recently. It is the extent, rather than the existence, of quarrying, coal-mining and iron-smelting that has tended to pass out of memory. I shall try to provide a brief introduction to these industries and to some smaller concerns: pottery, fireclay production, lime burning and vitriol manufacture. My survey cannot be exhaustive since I know very little about soap boiling, clay pipe production, nail making or leather tanning. I hope any reader with knowledge of these activities will feel free to contribute. Although my main interest is in the history of technology I am not unaware that the successes I shall describe came at considerable human cost. In the period selected the rural poor were driven by a need for work into factories and crowded, unsanitary, housing. Some employers, like Titus Salt, were humane men but others were exploitative. Foundries, mines and vitriol works were dangerous places where often little thought was given to worker safety. Those who paid the price of progress seldom reaped its benefits.

Bradford had many advantages as an industrial centre. Building stone was relatively easy to acquire, and since the late eighteenth century there had been a vigorous brick industry. Cheap local coal was available, and could be coked to supply blast furnaces which made pig iron from locally dug ironstone. There had long been water-powered corn and textile mills but it was the introduction of steam engine power that really transformed any process that was capable of mechanisation. Cloth production was a principle beneficiary of this technology which in turn promoted the development of textile engineering in Bradford and Keighley. The town was originally a communications backwater. It was hard to move raw materials, or manufactured products, cheaply and speedily. Horse transport had been used for centuries and a network of pack-horse routes had developed throughout West Yorkshire. The construction of turnpike roads in the years 1734-1825 produced a substantial improvement in the situation. With the opening of sections of the Leeds to Liverpool canal in the 1770s, with its spur into Bradford, transport of bulk goods, especially coal and limestone, became far cheaper. Railway links were established by the 1850s.

A 30.5 ton Rolling Mill flywheel presented by Alan Elsworth and preserved for display near the site of Low Moor Ironworks.

A century ago no community would be without its blacksmith but Bradford could boast a complete package of iron based technologies: ironstone mining, iron-smelting, and foundries. Historical sources, and deposits of slag, suggest that a medieval, bloomery furnace based, iron-smelting had occurred at Eldwick, Harden, Baildon, and Eccleshill, with charcoal being the fuel employed. Until their dissolution around 1539 northern Cistercian abbeys were heavily involved in iron-making but there is some documentary evidence of late Tudor smelting at Esholt and Hirst Wood, Shipley. The origin of modern industry was the discovery in 1709, by Quaker ironmaster Abraham Darby of Coalbrookdale, that iron could be successfully smelted using coked coal. This advance took about 50 years to be widely accepted. Darby’s grandson was the creator of the famous iron bridge.

An iron pig produced by Abraham Darby in 1756, on display at Coalbrookdale Museum.

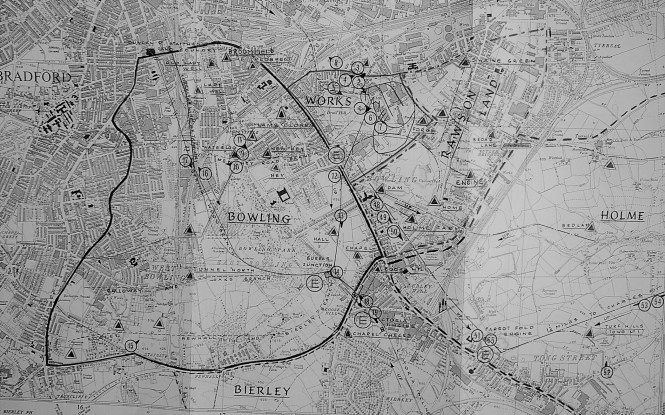

Bradford did not have the capacity to produce vast quantities of charcoal for blast furnace fuel but Darby’s discovery resulted in south Bradford’s Black Bed coal seam being mined for its rich roof deposits of ironstone. It was discovered that the deeper Better Bed coal seam was low in sulphur and phosphorus and so produced coke highly suitable for iron-smelting. The industry was capital intensive but blast furnaces were set up at Birkenshaw (1782), Bowling (1788), Low Moor (1791) and Bierley (1810). Their products were cast iron and the ‘best wrought iron’, produced by Cort’s ‘puddling’ process. Cannon and shot were manufactured during the Napoleonic Wars. At a later date the companies did not adopt the Bessemer process to convert cast iron into steel for which Sheffield became celebrated. The furnaces are long gone but the ‘dross’ waste and some of the iron products remains. I vividly remember encountering some Low Moor cannon at Alnwick Castle. As local deposits were exhausted mineral carrying tramways transported vast amounts of coal and ironstone for miles towards the furnaces. In the 1960s a scholar called Derek Pickles studied the mineral ways supplying Bowling Iron Works. His detailed and fascinating work is curated by Bradford Industrial Museum but I know virtually nothing about him. Can anybody help me?

A plan from Derek Pickles’s study showing mineral ways around Bowling Iron Works (top centre). The triangles mark collieries.

If you want to undertake further background reading the Local Studies Library has copies of three useful texts:

- RCN Thornes, West Yorkshire: A Noble Scene of Industry, WYCC (1981)

- Gary Firth, Bradford in the Industrial Revolution, Ryburn Publishing (1990)

- C Richardson, A Geography of Bradford, University of Bradford (1976)

Derek Barker, Local Studies Library Volunteer