Bradford is famous for spinning and weaving but textile production was only one of a group of important industries which ‘Worstedopolis’ supported. Since several are now almost forgotten by contemporary citizens I should like to draw attention to those which seem unreasonably neglected, in a series of short articles.

Limestone was a most valuable commodity. It could be cut into ashlar for building construction. It could be burned in kilns to produce quick lime which was then slaked with water. In either of these forms it could be spread on the land to ‘sweeten’ acid soils, making them more fertile. Slaked lime was also the essential ingredient of lime mortar, render and whitewash. To charge a blast furnace crushed limestone was added to coke and iron ore because it assisted in the separation of the slag waste. Some hard fossil-containing limestones which took a good polish, like Purbeck stone, were regarded as ‘marbles’ and used for decorative purposes. It is common today to employ limestone aggregate for path and road construction, but this is a relatively recent development.

Limestone consists largely of a single mineral called calcite (calcium carbonate). Immensely thick limestone strata are common near Skipton and in the Dales. Geologists recognise many sub-types of limestone classified by age, appearance, and fossil content. Since most of the stone reaching the Bradford area was burned we need not be too concerned these complexities.

Lime quarry at Stainforth, North Yorkshire.

Although limestone strata do not reach the surface in the Bradford area there was nonetheless an early lime-burning industry based on the extraction of boulders from glacial moraines in the Aire and Wharfe valleys. Boulder pits were well established in Bingley by the early sevemteenth century, and three groups of pits are still marked on the first OS map of the area (1852). In 1931 the Bradford Historical & Antiquarian Society published a series of West Yorkshire Deeds which are still available in the Local Studies Library. An indenture of 1604 between Alexander Woodde of East Morton and Abraham Bynnes, with others, mentions the ‘digging of greetstones’. In 1620 Thomas Dobson of Bingley leased four closes of land to his father Michael ‘with authority to dig there for lymestones and to burn, sell and dispose of them’. Glacial erratic limestone found elsewhere was almost certainly exploited in the same way. In the nineteenth century, on at least one occasion, the digging of a railway cutting seems to have exposed similarly valuable boulders.

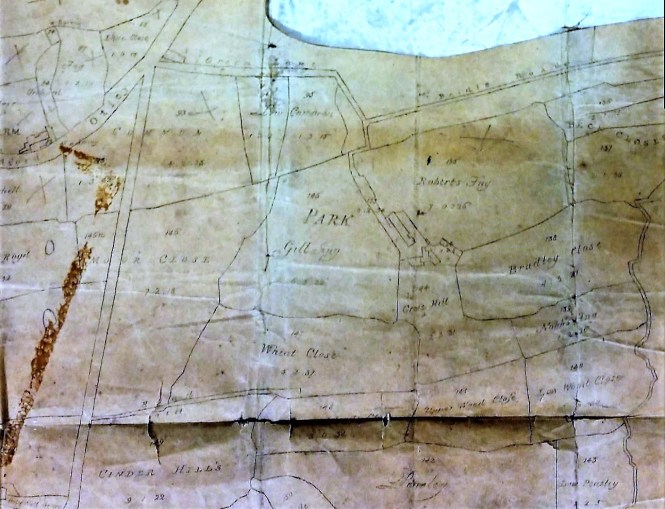

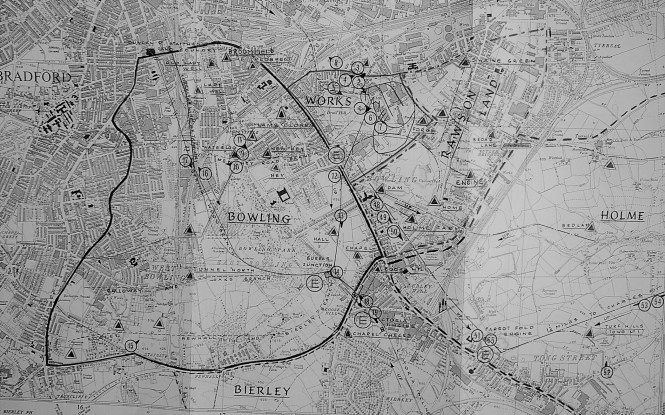

Lime stone quarry near Bowling Junction, and close to a mineral way to Bowling Iron Works. In this position it must represent the working of a moraine deposit (detail from 1852 OS map).

With the construction of the of the Shipley to Skipton sections of Leeds-Liverpool Canal (1773-74) plentiful supplies of limestone became available from the Skipton quarries. The cheap movement of limestone and coal were among the original ambitions of the canal promoters. Once you had supplies of limestone you required some means of burning it. Local scholar Maggie Fleming, is currently collecting information about canal-side lime kilns, and early lime-burning from erratic boulders, particularly at Micklethwaite and Bingley. Between 1774-83 the Bradford Lime Kiln Co. had eight kilns in Bradford at a site between Broadstones and Spinkwell Lock. There was evidently an extensive canal-side lime-burning industry since the first OS map also records kilns at, among other places: Silsden, Riddlesden, Micklethwaite, Crossflatts, Bingley (Toad Lane), Dowley Gap, and Shipley.

A map of 1863 recording lime kilns near the centre of Bradford.

There were a number of lime kiln designs including some very advanced Hoffman continuous kilns like the one preserved at Stainforth, N.Yorks. Simple stone built field kilns were once common in this area. They were charged with broken stone and coal from above, with quicklime and ashes being raked out from below. The field name ‘lime-kiln close’ or ‘kiln close’ may reflect this older lime-burning industry. There are two fields in Heaton with these names, now located in Heaton Woods. Local historian Tony Woods has studied Rosse archive records from Ireland and can demonstrate that Heaton coal pits were supplying a lime-kiln, somewhere near, with fuel as long ago as 1776.

Field kiln near Grassington

If you would like to do more reading on this topic may I suggest:

J.V. Stephens et al. Geology of the country between Bradford and Skipton, HMSO, 1953, 149-151, 149. This is essential reading for geological background to any local extractive industry.

David Johnson, Limestone Industries of the Yorkshire Dales, Amberley, 2010. It is inconceivable that anyone could ask a question about limestone that this book cannot answer.

Gerald & Sheila Young, Micklethwaite: the History of a Moorland Village. The early section of this book describes has an interesting account of the exploitation of local mineral resources.

Derek Barker, Local Studies Library Volunteer