Bradford is famous for spinning and weaving but textile production was only one of a group of important industries which ‘Worstedopolis’ supported. Since several are now almost forgotten by contemporary citizens I should like to draw attention to those which seem unreasonably neglected in a series of short articles.

In the nineteenth century Hunslet, Rothwell & Knottingley were noted West Yorkshire glass making centres. I was very surprised to find a reference to a much more local, and earlier, source of glass production in Francis Buckley’s book Old English Glass Houses, originally written in the 1920s. The best evidence he provided was an item taken from the Leeds Mercury of 1751:

To be lett: a very good glasshouse adjoining to Wibsey Moor, three miles from Halifax and two from Bradford with a very good farm-house and 22 acres of good land belonging to it. Also eight cottages for workmen to dwell in…….There is plenty of very good stone upon the place that grinds to a good sand, and is as proper as any that can be bought to make flint and crown glass with. Also very good coal within 300 yards of this glass-house at two pence per horse load.

At this time Wibsey formed part of North Bierley. Places, which by the nineteenth century were called Morley Carr, Wibsey Slack, Wibsey Low Moor or Odsal Moor, could then be described simply as Wibsey Moor or Wibsey Moorside. Low Moor itself didn’t exist as a location until after the famous iron works was established.

A glasshouse, which I suppose we would now call a glass-works, included a furnace for making glass from basic ingredients at high temperature. Glass is basically fused silica obtained from the mineral quartz, for which sand is a cheap and convenient source. Silica alone can make a glass but it melts at 1700°C which is difficult to reach. Since ancient times it has known that the addition of an alkali flux, such as natron (soda ash) or plant ashes, considerably lowers the temperature of fusion to a more attainable 1100°C. To give the glass stability lime or magnesia were also incorporated. Finally substantial portions of cullet, that is scrap glass, would also be included in the mix to help the other ingredients blend together. This was achieved in a fireclay ‘glass pot’. Firclay extraction is an industry I shall discuss on another occasion.

Crown glass was used to make windows; a crown was a flat disc of glass, produced by spinning a gather of glass on a blowing iron. From a crown small panes or quarries could be cut. Flint glass was used for bottles; it did not actually include flint as a raw material. The bottles would be hand blown into a wooden mould. Usually the two type of glass-making were kept separate by law, partly for taxation reasons but also because window glass was considered to be of greatly inferior quality. At various times glass furnaces were heated by wood or coal, although furnace design differed significantly depending on which fuel was employed. By the eighteenth century, in this part of Yorkshire, the availability of cheap coal was clearly an incentive for the potential purchaser of a glass-works.

The glass cone at Catcliffe, South Yorkshire.

The glass cone at Catcliffe, South Yorkshire.

Since we know that the Wibsey Moor glass works was constructed by 1751 we can be reasonably certain about its contents and appearance. In Britain the period 1730-1830 was the era of the brick glass cones which were built to enclose a central furnace, and the space in which firms of glass makers worked. The provision of internal working space is an important distinction from pottery kilns, which glass cones superficially resemble. In the UK only four cones now survive with the nearest being at Catcliffe in South Yorkshire, considered to be the finest example in Europe.

At Wibsey Moor (Low Moor) the builder of the glass-works was Edward Rookes Leeds (1715-1788) of Royds Hall, Lord of the Manor. James Parker in Rambles from Hipperholme to Tong states that in 1780 the works were demolished by another local land-owner Richard Richardson, together with some ‘freeholders’, as an infringement of their rights. Then, he says, it was re-erected on Leeds’s own land. Disagreements over the use of common land, or the exploitation of the minerals under it, between powerful local landowners was not uncommon before the Enclosure Acts. Parker’s account is credible but he is the only source for it. Considering the advertisement from the Leeds Mercury with which I started, 1750 is a more likely date than 1780 even if the rest of the account is true. Glass House’ remained as a place name in Low Moor although the cone itself was probably demolished in the late 1820s.

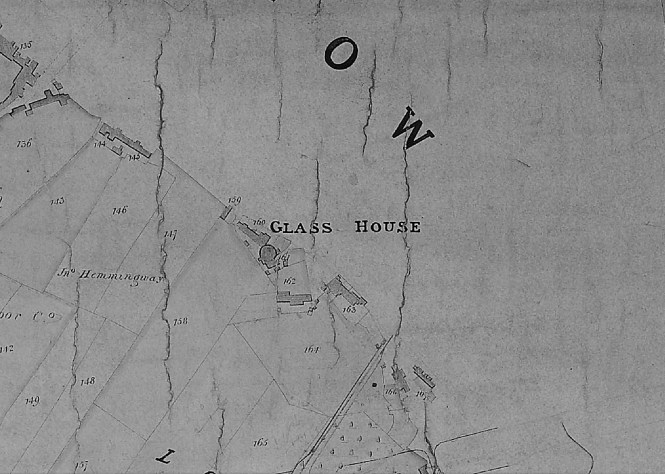

A detail of the Fox map of Low Moor showing a circular plan of the glass cone, with ancillary buildings. Other versions of this map exist in which this feature is not represented.

A detail of the Fox map of Low Moor showing a circular plan of the glass cone, with ancillary buildings. Other versions of this map exist in which this feature is not represented.

The ancillary buildings which seem to be represented in the plan would include storage space and an annealing furnace or lehr. A newly made glass object needs to be cooled down to room temperature very slowly, so that stresses produced by solidification of the glass could be dissipated. This is about as far as a student of technological history can take the Wibsey Moor glass house, but I am extremely fortunate to have had the assistance of Mary Twentyman of the Low Moor Local History Group. She believes she will be able identify the original glass-maker who leased the works, and hopefully establish something about his life. The Bradford glass industry is truly forgotten and has probably received only three brief written mentions during the last 150 years. Its full story may soon be told.

Derek Barker, Local Studies Library Volunteer