I’m not really a railway enthusiast so I must start with an apology to those readers who are, and say that I would welcome your guidance. I don’t find the early history of Bradford’s rail links an easy topic since the companies involved seem to change their names, and move the location of their stations, quite frequently. Naturally the creation of early railway lines generated maps and plans, many of which have survived. Even here I have a problem since tracks appear on maps which are notionally of an earlier date. Despite these difficulties I want to describe the early lines entering Bradford from the south because of the interesting light they shed on the city’s industrial past.

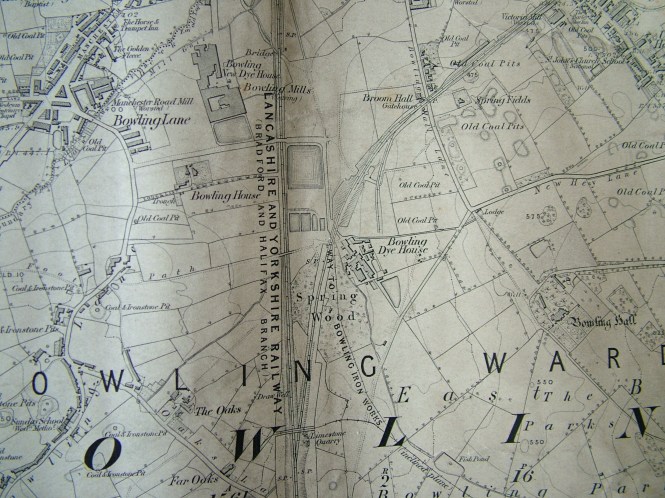

The first image is a detail from the 1852 Ordnance Survey map. It shows Bowling junction, although this is not named. Two, seemingly single, rail tracks, are mapped. The first is the Lancashire and Yorkshire Railway line which connected Halifax to Bradford, and its terminus Drake Street (later Exchange) Station which opened in 1850. The second line moving off to the right went from Bowling junction to Leeds, via Laisterdyke, and was opened a few years later in 1854. It was operated by the same company and, I presume, allowed trains to travel from Leeds to Halifax direct, by-passing Bradford completely. The track no longer exists but the line is visible on aerial photographs.

I am interested that at the junction a ‘limestone quarry’ is mapped. Limestone strata do not reach the surface in the city area but there was nonetheless an early lime-burning industry based on the extraction of boulders from glacial moraines in the Aire valley. Boulder pits were certainly established in Bingley by the early seventeenth century. It looks as if glacial erratic limestone boulders were found elsewhere, being exploited in the same way. In this case the digging of a railway cutting presumably exposed the valuable mineral. Plausibly these boulders were taken to the nearby Bowling Iron Company where crushed lime was used as a flux in iron smelting. Slightly further north is Spring Wood. The name has almost certainly nothing whatever to do with a water supply. ‘Spring’ was applied to a tree that had been cut off at ground level for coppicing. So Spring Wood was presumably an area of old coppice woodland. William Cudworth records that there was once also a Springwood Coal Pit, but the wood itself soon disappears from maps.

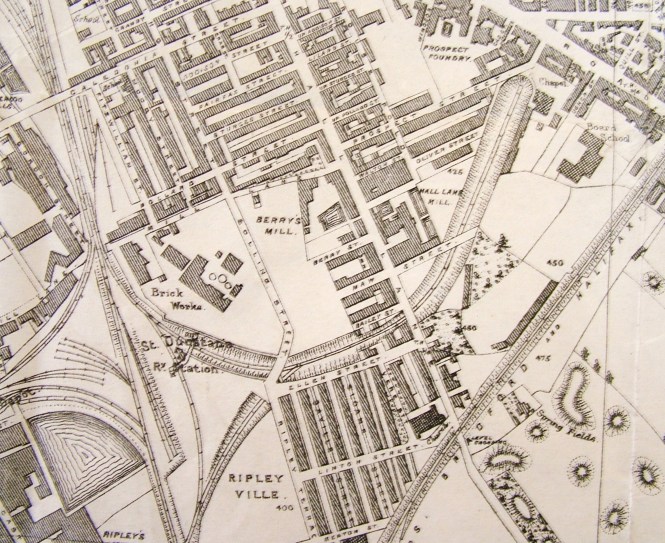

The next plan is from the Local Studies Library reserve collection. If you imagine it turned 90º clockwise it is clearly the same view as before. You can easily identify the two railway tracks and also the Bowling Dye works. The name of the company involved here is West Riding Union Railway. As I understand it this title was only employed for a brief period around 1845-47. This and other evidence suggests that this map is a few years earlier than that of the OS map we have examined. This map shows the Bowling Iron Company colliery tramway very clearly. This took coal to the Bowling Depot on Queens Street where I assume it was available to local merchants. The Bowling Dye Works and the Bowling New Dye House were both parts of the Ripley family enterprises (Edward Ripley & Co). What are obviously missing are the large reservoir and dye pits which are such a prominent feature in the OS map. When were these created? The Bradford Observer reports a large sale of land in this area, including that piece accommodating the Dye Works, in 1850. The vendor isn’t stated but might well be the Bowling Iron Company. Probably the dye works boss, the famous Sir Wm. Henry Ripley, purchased land at this time to allow for the expansion of his business and the assurance of adequate soft water supplies, which included a reservoir. Cudworth records a 100 acre purchase by the Ripley company and also states that a contractor called Samuel Pearson constructed reservoirs for Bowling Dye Works and Bowling Iron Works at a date ‘early in the fifties’. We shall hear more of Samuel Pearson shortly. Marked on this map are marked a variety of planned new streets. Were these streets ever constructed? Presumably not. After 1863-64 Ripleyville, consisting of 200 houses with schools, was constructed by Sir Henry but the alignment of these streets on the 1887 borough map looks quite different.

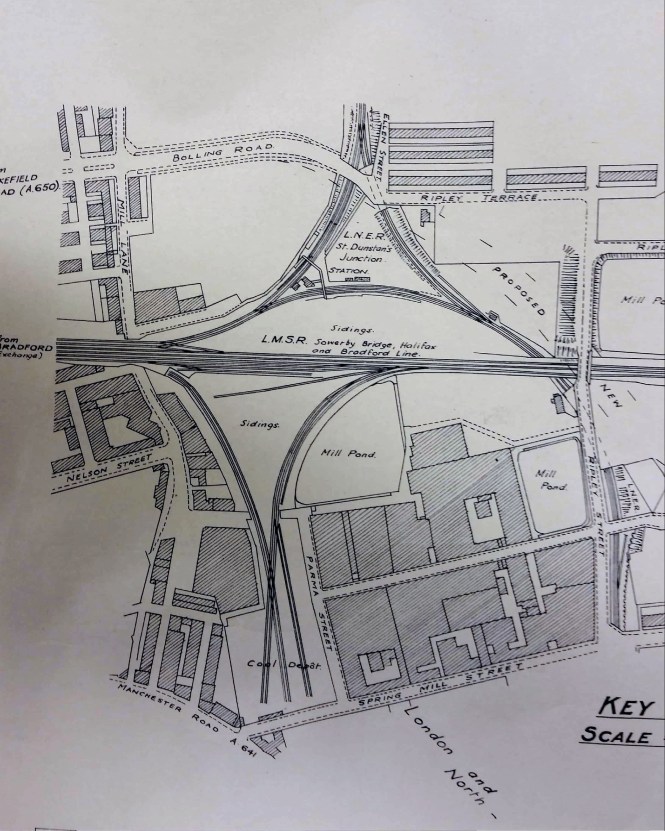

This third map shows an area slightly further north. There have been additional train track developments. The Great Northern Railway had opened its service to Leeds from Adolphus Street station in 1854 but the rival Midland Railway service, via Shipley, ended at a station more convenient to the town centre depriving GNR of customers. In consequence, around 1867, a track loop was constructed connecting the GNR line to the L&Y track at Mill Lane junction and allowing passengers from Leeds access to Exchange Station. Nearby St Dunstan’s passenger transfer station was also opened. The loop is clearly visible on the map north of Ripleyville. In describing the work involved in taking the GNR railway line from the Exchange Station towards Leeds, Horace Hird (Bradford in History, 1968) again mentions the activities of Samuel Pearson & Son who took over responsibility for the material excavated from the necessary cutting. The cutting spoil created a ‘great mound’ and for 15 years 60 men were employed making drain pipes, chimney pots and bricks from this material. Their Broomfield brick works is clearly indicated on the map above the loop. The line seen curving away to the left edge of the map, opposite the brick works, services a series of coal drops which are still visible, in a ruinous state, off Mill Lane today.

Samuel Pearson was a Cleckheaton brick-maker who founded a contracting dynasty. His contracting business started in Silver Street, off Tabbs Lane, Scholes, in 1856. By 1860-63 Messrs. S. Pearson & Son were established at the Broomfield Works, Mill Lane (near St Dunstan’s) for the manufacture of building bricks, sanitary tubes and terracotta goods. The works can be identified on the 1871 map of Bradford but closed shortly before the 1887 map was published, the ‘spoil bank’ being exhausted. The site is described as a ‘disused brick-works’ by the time of the 1895 OS map. Within a generation Pearson’s had became an international contractor and was particularly associated with Mexico during the dictatorship of Porfirio Diaz. Canals, railways and oil were among the company’s many interests. After being created a baronet Samuel Pearson’s grandson, Weetman Pearson, became the first Viscount Cowdray in 1917. The family seat became Cowdray House and park, near Midhurst in West Sussex.

For the final plan I return to the LSL Reserve Collection. Essentially it shows the same area as the last. The plan is undated but the railway companies have their pre-nationalisation names, so it is earlier than 1948. Wakefield Road is referred to as the A650 and local historian Maggie Fleming suggests that this nomenclature makes the plan later than 1920. St Dunstan’s Station is still present, and in fact had another thirty years of life before closing in 1952. The site of Broomfield brick works is blank, and is today a car park. The purpose of this plan seems to have been to show the course of a new road joining Bolling Road to Upper Castle Street. This is another thoroughfare that was never constructed.

Derek Barker, Local Studies Library Volunteer