The Old Inquirer [The Rev. Wm. Atkinson] A volume of tracts.

B 042 ATK (Please quote this number if requesting this item.)

In my trawl through the basement of Local Studies Library I came across a volume of tracts by ‘The Old Inquirer’. The use of pseudonyms was quite common in the eighteenth and nineteenth century, especially for authors writing on controversial topics or opposing the views of other writers. The Old Inquirer did both. His spat with ’Trim’, the Headmaster of Bradford Grammar School in the years from 1787 to 1791 was very public, bad tempered, and yet clever – both Trim and the Old Inquirer were well educated and highly literate. The prose (and sometimes verse) is fun to read even if we don’t fully understand what it was they were arguing about! The Old Inquirer was a prolific writer: the volume I came across had 16 separately paginated tracts containing some 70 individual letters, essays and other items. He even had his own printing press!

To provide extracts from these writings would be far too ‘heavy’ for these ‘Treasures’. Instead I have extracted some of the verse he used to illustrate his opinionsand which can be enjoyed just for themselves. They are indicative of the rumbustious satire of The Old Inquirer.

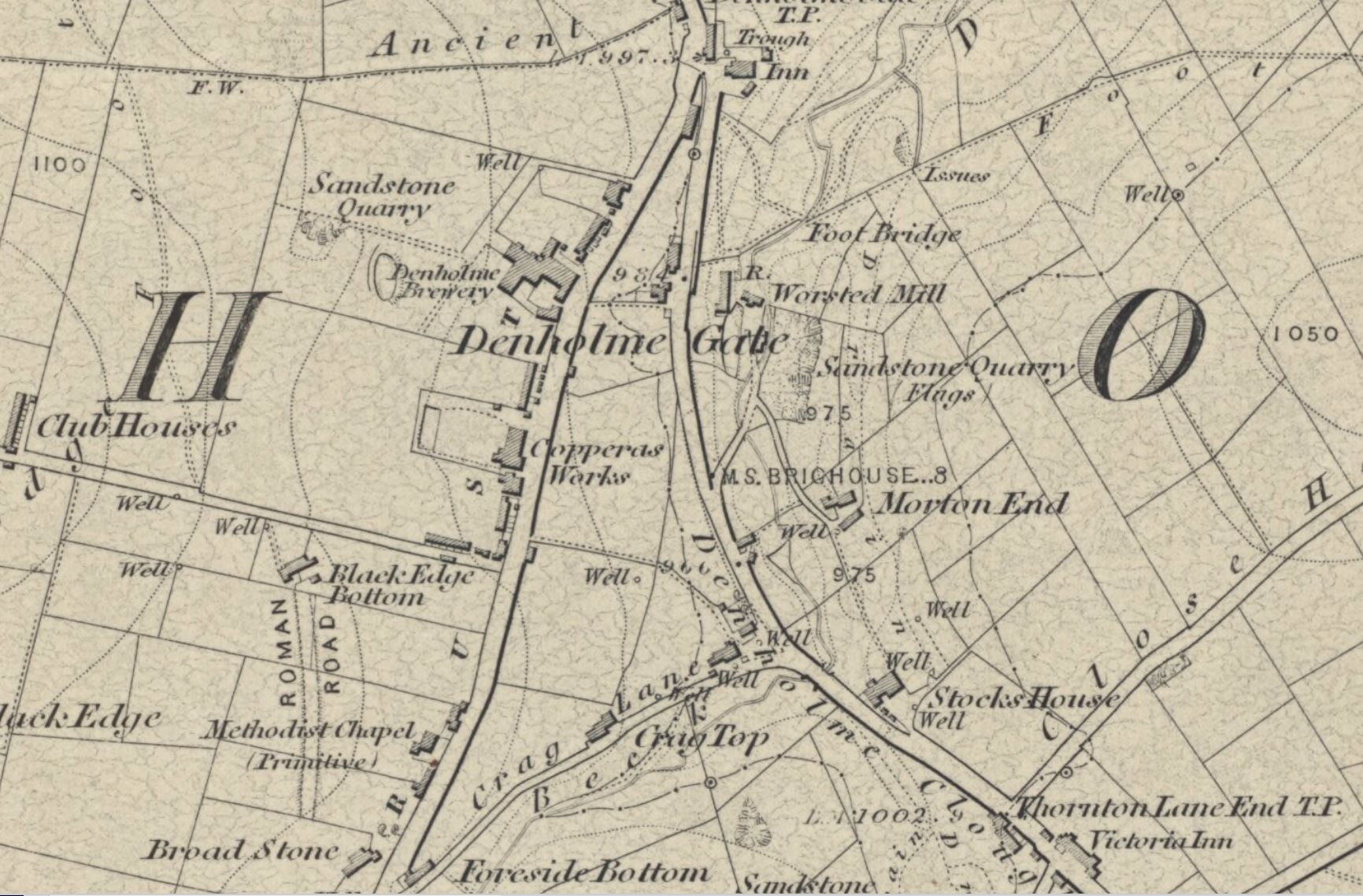

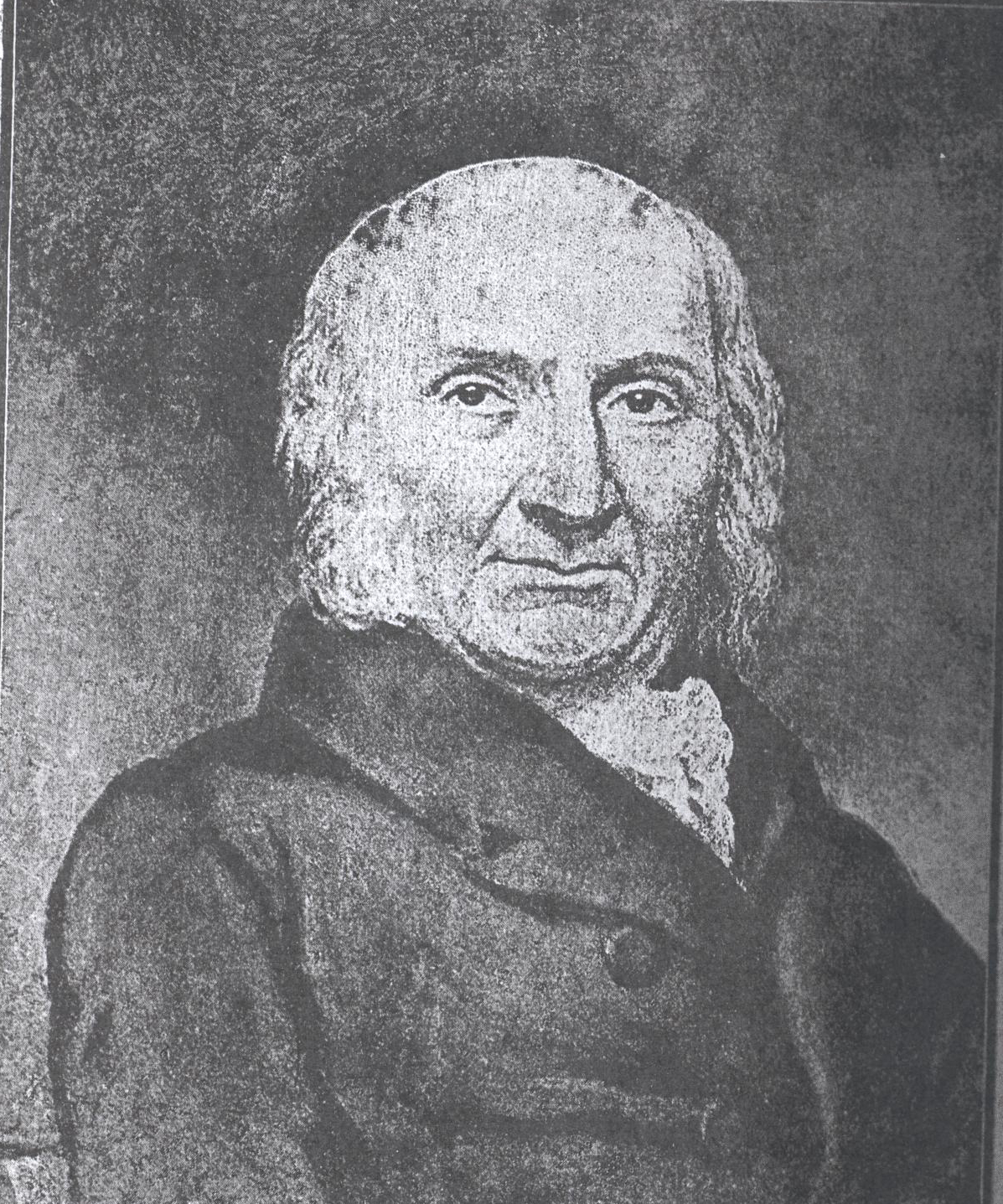

‘The Old Inquirer was the Reverend William Atkinson, M. A. , ‘Lecturer’ or ‘Afternoon Man’ at the Parish Church in Bradford (now the Cathedral) from 1784 till his death aged 89 in 1846, a period of 62 years. The ‘Afternoon Man’ was so-called because he was only required to be in attendance on Sunday afternoons. According to newspaper cuttings in the Local Studies Library, Atkinson was a man of herculean build and of singular strength of mind as well as body. He used to walk from his home in Thorpe Arch on Saturdays and walk back to his home on Mondays, staying over in Bradford for his Sunday lectures. So what did he do for those 62 years? Well, among other things, he wrote letters, essays and poems.

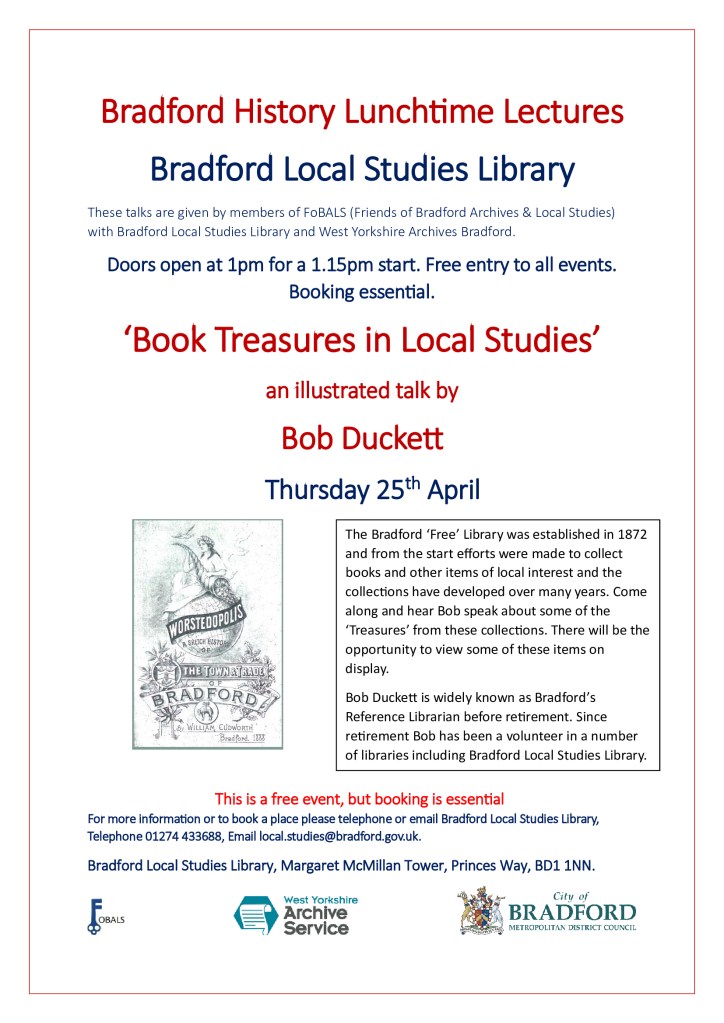

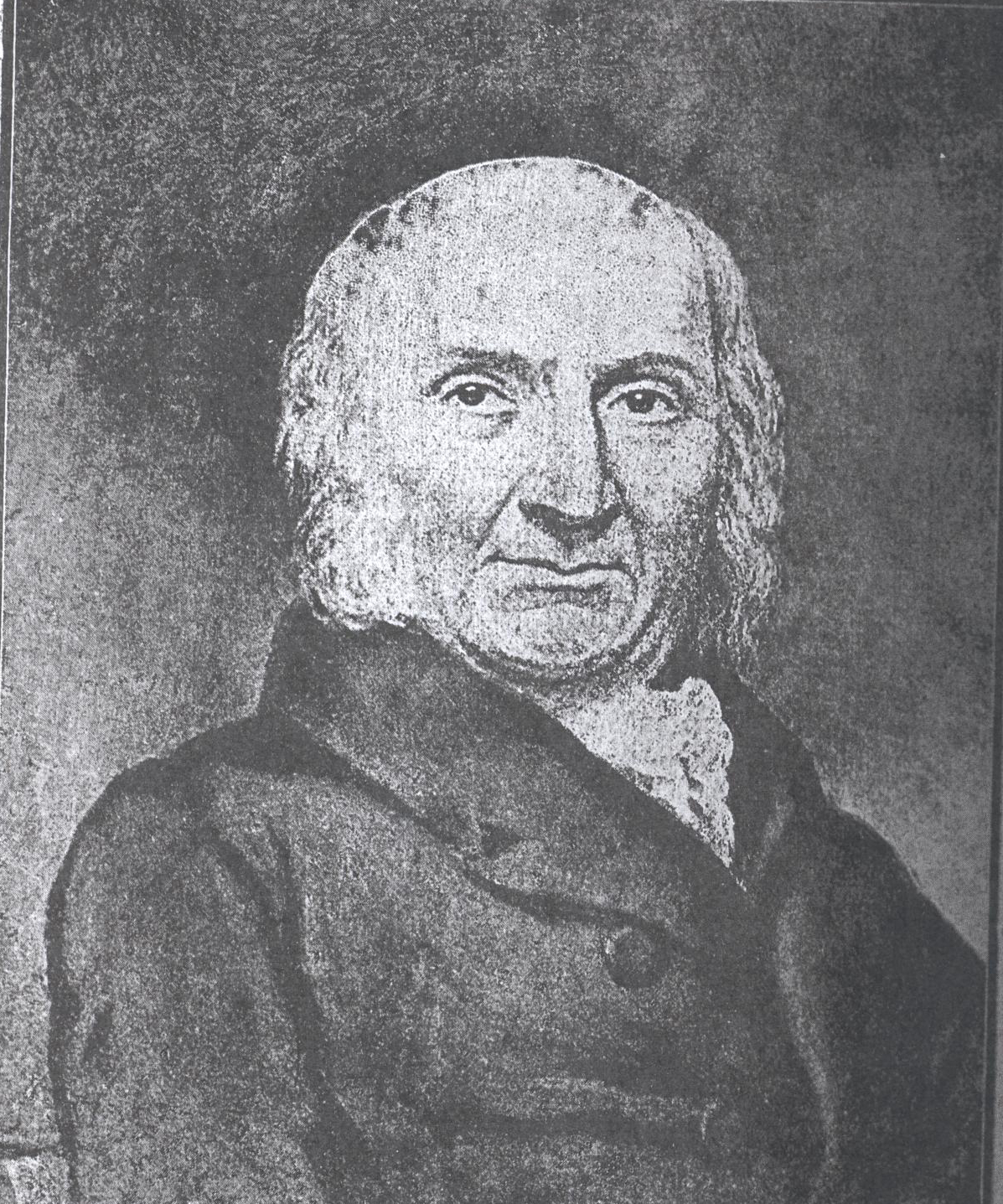

‘Rev William Atkinson’ from ‘Bradford Fifty Years ago, 1807’ by William Scruton

‘Parish Church and Vicarage in the year 1810’ from ‘Pen and Pencil Pictures of Old Bradford’ by William Cudworth

The range of subjects he wrote on was wide: the exportation of wool; tithes; political reform; dissenters from the Church of England; the Pope; press bias; agriculture; even banking. Anyone interested in understanding our history from 200 years ago would do well to read these tracts. Here, though, we just relish his gift for verse and satire, and be amused at the wit, boldness, and candour of the ‘Old Inquirer’. And maybe wish he was around today!

… Fee fau fum,

I smell the stink of democratic plum;

And though I love Reform disclosed,

And would by no means clog them;

Yet meeting with bare r – ps exposed

I cannot help but flog them.

(A Letter to the Reforming Gentlemen. 1817, p. 1. Tract no. 5)

Their arms, their arms,

Are the Radical charms,

With which they’ll lay about them;

Order, order,

Says R. D. our Recorder,

They’d better be quiet without them.

(Free Remarks upon the Conduct of the Whigs and Radical Reformers in Yorkshire; with some Slight Allusions to the Court Party, 1819, p.1. Tract no. 7.)

How Johnny Bull

Is made the Gull,

Of Men who love his money,

The wasps who thrive,

Within his hive,

And live upon his honey. (p.12)

(Remarks on the Strictures in the Leeds Mercury upon the Rev. M. Jackson’s Coronation Sermon, &C. &c. &c., 1821. p. 12. Tract no. 7)

A Lily sprung in foreign land,

And grew to be a flower,

It was transplanted to this strand,

But flourish’d not an hour.

(As above, p. 16)

“Alas! No rest to mortal man is given,

Till they are safe arriv’d in heaven.”

(A Speech Intended to have been spoken at a Second Meeting of the Clergy upon the Popish Question, 1821, p 41. Tract no. 13)

The man in the moon,

Has ordered a spoon,

To give all there maniacs their pottage;

No, no, let them go

To the region below,

For the pickle-pot must be their cottage.

(As above p. 51)

I am the Prince’s Dog at Kew,

Whose Dog are you?

(A letter to the Reforming Gentlemen, 1817, p. 14. Tract No. 5)

Granting that he had much wit,

He was rather shy of using it.

(As above, p.13.)

Hallo, hallo, away they go,

Unheeding wet or dry,

And horse and rider snort and blow,

And stars on all sides fly!

Hold Parsons, hold, on Peggy’s rig,

For stormy is the wind,

Or like John Gilpin’s hat and wig,

You’ll soon be left behind.

(A Letter to one suspected to have been written by a Stranger, assisted by the Jacobin priests of the West Riding, 1801, p. 43. Tract No. 1)

Your reasoning, with wondering stare,

Quoth Tom, is mighty high, Sir;

But pray forgive if I declare,

I doubt it is a lie, Sir:

We ne’er shall get, I really think,

Lord H….w..d’s land to us, Sir,

I’d rather have a pot of drink,

Than hang up like a truss, Sir:

If you think thus, my honest clown’

We’ll take another sight on’t –

Just turn the picture upside down,

And you will see the right on’t.

(Lucubrations in Prose and Verse written during the Awful Revolution in 1829, p. 12. Tract no. 16)

Jerry’s Song to his Tippling Wife.

Upon her cheek so fair,

The lily and the rose,

Of flowers a pretty pair,

Did all their sweets disclose.

But time has cropt that rose,

The lily too doth fade,

Such are the cruel foes;

In wedlock to a maid.

And has time cropt that rose?

Ah, no! it grows it grows,

Upon her well-fed nose,

You yet may see my pretty little rose.

(As above, p.13)

And what of the Frogs, Billygoats, and The March of Reason of the heading to this blog? See:

Tract number 14: A Rapid Sketch of Some of the Evils of Returning to Cash Payments, and the only remedies for them. To which are added The Leeds Mercury turned into a Frog, the Billygoats in Leading-Strings, and The March of Reason. 1823.

A full listing of Atkinson’s tracts can be found in the folder ‘Federer, Dickons and Empsall tracts in the Local Studies Library’. Listed under B 042 ATK

Stackmole