FERRAND, William. Memorable Speeches of William Ferrand, Esq. Reprinted from The Devonport Independent and Plymouth and Stonehouse Gazette of April 21st 1860. 16 pp.

(Please quote this number if requiring this item: JND 196/5)

It seems odd that a collection of memorable speeches by a prospective Member of Parliament for Devonport and Plymouth on the south coast of England in 1860 should have been collected by a Bradford historian. And also odd that the candidate should be heir to an estate in the Aire Valley 300 miles distant! But William Ferrand was no ordinary person.

William Busfeild Ferrand, Esq. (1809-1889), was heir to a prosperous Airedale estate of over 2,000 acres centred on Harden Grange (St Ives), Bingley. He entered politics as a right wing Tory, upolder of the rights and virtues of the English squirearchy, yet a supporter of Richard Oastler’s ten-hour movement and the campaign to reform factory conditions. He was an outspoken champion of the working classes, favoured economic protection, and was opposed to the new Poor Law. After failing to get elected as Bradford’s MP in 1837, he succeeded at Knaresborough in 1841, but lost his seat in 1847. After two failures in Devonport, he finally succeeded there in 1863.

Ferrand was a formidable speaker, both in open air public meetings (‘Iron Lungs’) and in Parliament. There he promoted the interests of the industrial and agricultural workers, notably in his ‘Bill for the Allotment of Waste Lands’. In this he wanted land that had not been enclosed to be given to the poor for them to cultivate, land we now know as ‘allotments’. The Bill never became law, but Ferrand’s support of the working classes earned him the epithet of ‘The Working Man’s Friend’. It had also attracted the attention of Benjamin Disraeli, who was to become Prime Minister in 1868.

In October 1844, Disraeli and Lord John Manners stayed at Harden Grange. These two were members of the’ Young England’ group of dissident Tories, who had ideas in common with Ferrand. Of particular interest is that some local Bingley and Aire Valley locations and characters appear in Disraeli’s novel, Sybil, published in 1845. Writes Robert Blake in his biography Disraeli:

Much of Sybil is devoted to the conditions of the working class in the great manufacturing capitals. Disraeli probably obtained a good deal of local colour in the course of a prolonged stay in the north … He … visited … William Busfeild Ferrand, M.P., at Bingley. Ferrand, a man of most intemperate language, was a stout alley of Young England and a great expert on the malpractices of manufacturers and millowners.

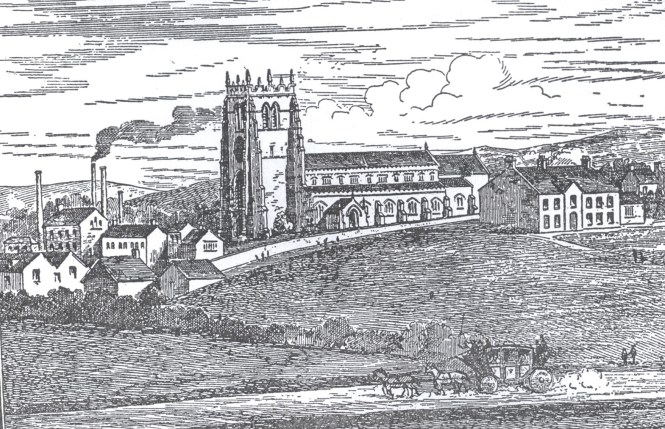

Harden Grange (St. Ives)

While Disraeli was at Bingley, there was a ceremonial opening of some land given by Lady Ferrand to the community as an allotment in Cottingley. Part of the celebrations was a cricket match in which Disraeli, a future Prime Minister of Great Britain, partnered the local shoemaker in a winning last wicket stand! This event does not appear in Ferrand’s Memorable Speeches, but is a local event of interest.

Five of Ferrrand’s speeches are reported in this pamphlet. In his ‘Speech at the Dinner’:

He said he brought that notorious system [the truck system] before the House of Commons, and though the cotton lords first denied the truth of his representation, yet when he produced an enormous packet of ‘abatement tickets’ they all sat as mute as mice with a cat in the room. (cheers). He convinced those men of the atrocious cruelty, and the truck system was put down by the legislation. (cheers)

Ferrand also covered the evils of the long hours worked by children in the mills and factories, and much else. These ‘Memorable Speeches’ are worth reading for those wishing to learn more about nineteenth century social and industrial history. And for learning more about this remarkable local celebrity.

Stackmole