Wibsey sits to the south-west of Bradford, at the top of one of the hills leading out of the city. The village actually stands at quite a height. Looking at an Ordnance Survey map, the 850ft contour line passes through the roundabout at the top of St Enoch’s Road and the land rises to 975ft at Beacon Hill. This must be one of the highest extensive urban areas in Britain. The population in 1991 was 5,357.

The village was mentioned in the Domesday Book as Wibetese. At that time the manor was granted to Ilbert de Lacy by William the Conqueror. The origins of the village name are still uncertain. It has been suggested that the name is an adulteration of “Wigbed’s Land” or “Wigbed’s Height”.

The manor of Wibsey at that time had a common, and the village was surrounded by the Forest of Brianscholes. This was a dense, dark place which offered cover to wild boar and even wolves. Villagers had to have their wits about them on dark nights.

The monks of Kirkstall Abbey established the famous Wibsey horse fair. Drovers came here from all four corners of the British Isles to buy and sell horses. The fair’s heyday seems to have been at the start of the 20th century, before the start of World War One. Horses were run along Fair Road, Folly Hall Road and Reevy Road. Additional markets selling various goods spread down Market Street, High Street and Smithy Hill, and even into the fields to the south of the village. You could buy anything from pots and pans to the famous Wibsey geese. There were also traditional fairgrounds, spectacularly lit at night. Much safer to wander around at this time than when the village was surrounded by the forest. The fair usually lasted from 5 October to 20 November. The final day was known as the ‘Ketty Fair’, on which all the horses and animals in poorest condition were sold off.

Wibsey Slack was home to the famous geese. They used to roam here quite freely and unconfined. It used to be regarded as a sign of impending bad weather if the geese left the slack and wandered into the actual village.

One of Wibsey’s most pleasant areas is its park. It is around 30 acres in size and was opened on 25 May 1885, after a grand ceremony. It has always been a popular recreational area with locals. There are sports pitches, a lake, flower gardens, children’s areas and an aviary. The park was once home to a strange attraction. In the 1930s visitors to the park were invited to relax in a ‘sitting room’ sculpted from plants and hedges. This novel arrangement was one of many sculptures produced by the first park keeper, James Walton.

Wibsey Park was built on Wibsey Slack. The area was to be enclosed by the lords of the manor in 1881, but a local councillor, Enoch Priestley, fought against this for the rights of the local people. The land was saved and the park created. Enoch Priestley became a local hero. He also campaigned for a new road linking the village to Bradford. When the road was completed Priestley was unofficially canonised by the locals. They named the road St Enoch’s in his honour.

Wibsey has had a varied industrial history. It was a popular coal mining area, though it seems the coal was of poor quality and was only mined near the surface. The Industrial Revolution arrived here in 1836 with the opening of the first mill. One of the famous characters of this time was Joseph Hinchcliffe. He ran the Horton House Academy and in 1826 started up a Sunday School in the old chapel on Chapel Fold. The school had over 100 pupils and helped boys and girls whose religious instruction would otherwise have been neglected. Hinchcliffe carried out his teachings until ill health forced him to retire in 1834. However, no one came forward to replace him in the Sunday School, so rather than let the children down, Hinchcliffe decided to carry on teaching them from his home at Horton House. He was also a generous man. Every Christmas he treated the children to a Christmas dinner and each winter he would go round to the homes of the more needy boys and girls and instruct their parents to buy them new clothes at his expense. A true Samaritan of his day!

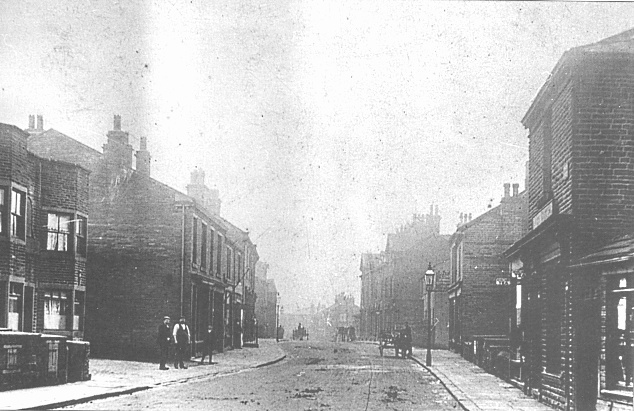

Today Wibsey is a popular commuter suburb for the city. The past seems to rub shoulders with the present here. Cobbled streets and ancient cottages still exist, many bearing the dates of when they were built. Wibsey has its modern face too. It has a thriving nightlife, based on the pubs on the High Street, such as the Ancient Foresters, Swan and the Windmill. People travel from all over Bradford and from further afield, for a night out here. The village has all the shops and services you could wish for, mostly situated along the High Street. In fact you could live here quite comfortably without ever having to visit Bradford. This has helped Wibsey maintain a ‘village’ feel, even though it is only a few miles from the city centre.

Wibsey High St. c.1900

High St. 2002

This information was taken from “The Illustrated History of Bradford’s Suburbs“, by Birdsall, Szekely and Walker