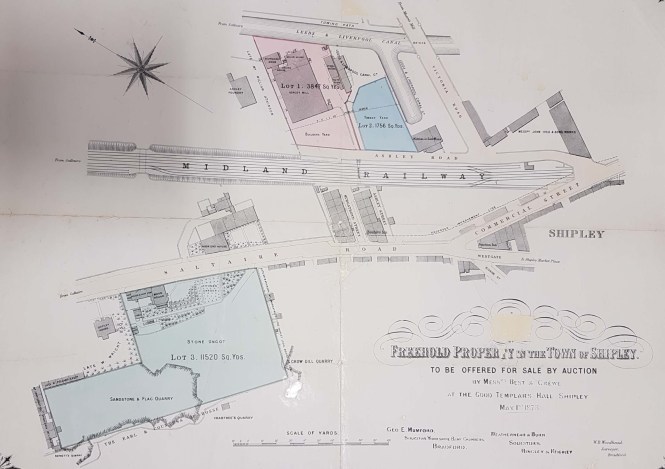

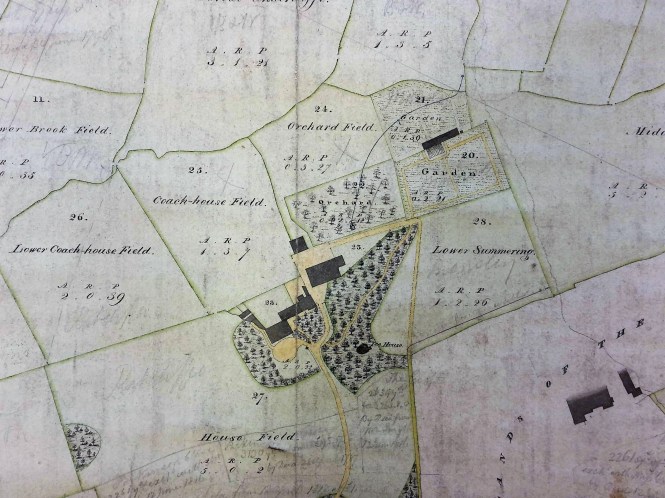

This plan features a site at Dubb Lane, Bingley adjacent to the Leeds and Liverpool canal. It was drawn up by a surveyor, E.S.Knight, in 1853 when the freehold property was to be sold by auction at the Fleece Inn. Sale plans are a significant source of the Local Studies Library’s reserve collection maps, and the buildings or property surveyed in such plans are naturally displayed in far greater detail than in contemporary Ordnance Survey maps. This complete plan should generate a LSL classification of BIN 1853 KNI and indeed there is such a card in the map index file. I cannot find the plan itself however so possibly this reserve collection example is the only copy now available. The main building is clearly labelled Dubb Mill and shows a steam powered corn mill with an adjoining residence. To reinforce this material it was not difficult to find the same auction being advertised in the Leeds Mercury. The mill was apparently three stories high and the house, stables, mechanics’ and blacksmith’s shops were also listed. The grinding was seemingly undertaken by six pairs of French stones. The benefits of the location, close to the canal and railway, are made clear. Mr E.S. Knight, was a land surveyor of Queensgate in Bradford. Particulars concerning the property are said to be obtainable from George Beanland of Great Horton. Identifying him was my first difficulty. There is a man of this name in Horton at the time of the 1861 census who is an agent but George Beanland of Messrs. George, Joseph and John Beanland, corn and flour dealers of Beckside, is perhaps more likely to be the man involved. Unfortunately no owner or vendor of the corn mill is mentioned by name but at the time of the sale the yearly tenants are Messrs William England & Son, and the under-tenant one Jonathan Cryer. According to the London Gazette, in the following year the partnership of William England & Son of Bingley was dissolved and the assets were transferred to brothers Abraham and William England. Interestingly the newspaper advertisement promotes the idea of converting the corn mill to cotton or worsted spinning, which is very pertinent to my subsequent analysis.

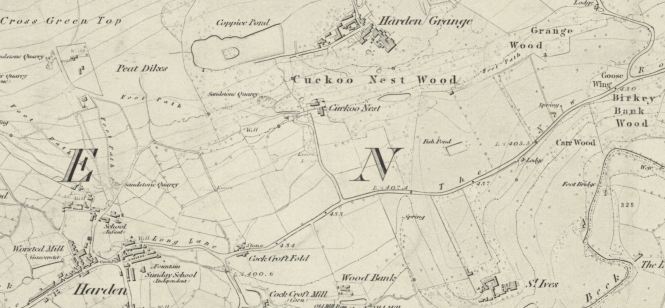

I think that we can be sure of the mill’s earliest possible date of construction since it is so closely aligned on the canal. This canal section was completed by 1774. The shape of the site, and its position adjacent to a canal bridge, makes it easy to identify in other maps even if the buildings are unnamed. There is no doubt that the mill is present in the earliest map available to me, the 1819 Fox plan of Bingley, but if Dubb Mill was always powered in the same way it cannot have been as old as the canal since the first steam powered corn mill was only built in Bristol five years after the canal was opened. Moreover the 1819 building block plan does not seem to allow for the engine and boiler house, yet what other power supply could there have been? I should say that it was by no means unknown for corn mills to be converted to textile mills, although was rare for conversions to move in the opposite direction. Some 35 years after the mill sale, in the OS 25 inch map of 1889, there is simply a warehouse at this situation which appears to be part of Britannia Mills. At that date, if you crossed the bridge and walked along the towpath on the opposite side of the canal in the direction of Bingley town centre, you would pass Ebor Mills (worsted) to reach a second worsted mill by then itself called Dubb Mill.

A few years before our plan, in the first OS map (surveyed in the late 1840s), the older Dubb Mill is naturally present although no indication is given of its function. At the position where in 1889 there was situated what I might call ‘new’ Dubb Mill there are three buildings labelled as cotton mills. A later map suggests that these units were also called Dubb Mills, which must surely have caused confusion. It may come as a surprise that cotton is being processed in an area so strongly associated with worsteds but in fact Keighley was a centre for the cotton industry in the early 19th century.

Establishing the history and ownership of the Dubb corn mill up to the time of its 1853 sale was the problem I set myself. An obvious source of information was Harry Speight (Chronicles and Stories of Old Bingley, 1898). He mentions a man called Robert Ellis, who seems to have been the brother of Bradford Quaker James Ellis. Robert took ‘the old Dubb corn mill’ about 1818 and was joined by James in 1822. Is this the same Quaker James Ellis who was so active in famine relief in Connemara in the late 1840s? Probably: Ellis & Priestman were partners in corn milling at Queen’s Mill, Mill Bank, Bradford which I believe vanished when Sunbridge Road was constructed. Speight also describes the construction of an ‘early worsted mill’ with an attached residence by Joseph and Samuel Moulding. This would certainly be an accurate description of the building on our plan in all respects except for the type of mill involved.

Speight wrote that about 1825 William Anderton took part of this mill but soon began building premises of his own in Dubb Lane for wool combing and spinning. These later buildings, he wrote, were later occupied by ‘the Ellises’ who raised and enlarged them for cotton spinning, and a new mill was built on the opposite side of the road which for some years (in the late 19th century this would be) was occupied by Samuel Rushforth JP. We seem then to have four mills to explain: the old Dubb corn mill, an early worsted mill constructed by the Mouldings, the Anderton-Ellis mill, and the Rushworth new mill which is perhaps the ‘new’ Dubb Mill. I’m not claiming that they all were in in operation simultaneously, nor that they retained one function during the full periods of their existence. I cannot see that the brothers Ellis took on our corn mill since Speight describes their corn mill as ‘old’ in 1818 when ours was spanking new. If our mill was constructed for textile manufacturing is it likely that the building would subsequently have returned totally to grain processing? The best evidence that touches on this point is the 1865 Smith Gotthardt plan of Bingley.

The detail is inverted but allowing for this you can clearly see that twelve years after the 1853 sale our mill is still present and is unquestionably labelled as Moulding Mill and the cotton processing units as Dubb Mill. It seems likely then that Speight’s second statement is correct and some members of the Ellis family actually moved to the Anderton worsted mill. I tried to obtain further information about these mills from the on-line 19th century copies of the Bradford Observer and Leeds Mercury. Unfortunately many entries and advertisements simply mention ‘commodious mills at Dubb’, providing neither mill name nor owner. Nor did trade directories provide simple answers. The 1822 Baines directory at least suggested that several characters in our story have an interest in the licensed trade: J & S Moulding were at the Shoulder of Mutton, Bingley and W Anderton at the Pack Horse, Cullingworth. I know that Mr William Anderton (1793-1884) certainly came from Cullingworth, even if he wasn’t the publican mentioned in my last sentence. His Bingley enterprise features in the Factories Inquiry Commission of 1834. His premises were described as steam powered and undertaking worsted yarn spinning. There were 56 people employed (16 under 12 years of age) which seems reasonable for a small mill. The employees’ hours of work were 6 am-7.30 pm. The machinery was stopped for a dinner break of 45 minutes at noon. There were six holidays per year (8 days total) when whole factory ‘stood’ and no wages were paid. Anderton’s mill is described as Dubb Mill, Bingley ‘a mill erected in 1819’ so I am reasonably sure this is the mill in our plan.

Inconveniently 1842 White’s Leeds & Clothing District directory does not record any corn millers working in Dubb, but William Anderton and Joseph Moulding are given separate entries as worsted spinners & manufacturers. Helpfully there is a small item in the Bradford Observer from 1848 to the effect that asignees of John Robinson, a Moulding tenant, were trying to sell power looms and machinery but this attempted sale would be prevented by ‘executors of the late Joseph Moulding’. It seems unlikely that such a building would have been re-equipped as a corn mill before being sold five years later but I cannot think of another explanation that fits. In 1843 a Joseph Moulding (1775-1843) of Dubb was buried at Bingley Parish Church.

Meanwhile life at William Anderton’s mill was not without incident. In 1850 the Bradford Observer recorded an assault on Fanny Broadly which arose from a ‘dispute over bobbins’ at Dubb. In the census of 1851 William Anderton is living at Wellington House, Wellington Street. He describes himself as a worsted spinner & manufacturer employing 240 males 265 females. This sounds like a reasonably large operation and must surely indicate new premises. Remarkably 30 years later William Anderton was still alive, at the age of 88, and living with his daughter Mary and son in law John Brigg (another textile man) at Broomfield House, Keighley. As I have mentioned Anderton’s mills were taken over by the Ellises of Castlefields Mill for cotton spinning, and their operation presumably represents the cotton mills present on the first OS map of the area. At the end of the century the name Dubb Mill is associated with Samuel Rushworth JP, woolspinner and manufacturer. Rushworth was a famous teetotaller who died in 1896 aged 52. His mill must have been the new construction mentioned by Speight. I assume that this is the new Dubb Mill on the 1889 OS map.

I have tried to pull all this together. There must have been an old corn mill in Bingley, possibly close enough to the river Aire to use water as a power source. Castlefields Mill was constructed in the late 18th century and by 1805 was run by Lister Ellis who stayed until 1829. In 1818-19 Messrs Joseph & Samuel Moulding constructed the first Dubb Mill. If it was a worsted mill hand-combing and weaving seem quite likely at that period. William Anderton may have later been involved with this building but by 1825 he was building his own mill nearby in Dibb Lane for wool-combing and spinning. William and James Ellis took this over for cotton spinning and Anderton must have used other premises. In the later 19th century Samuel Rushforth, who had started life working for Anderton, adapted the cotton mills and rebuilt a new Dubb Mill. My guess is that once steam power was introduced at the old Dubb mill it could function either as a corn mill or worsted mill and performed as both at various times. It clearly survived until 1865 but was later converted into warehouse, or rebuilt in that capacity by 1889. I know that interest in local history is very strong in Bingley and I’m hopeful that somebody will be able to put me right on aspects of this complicated story especially the matter of how many men called Ellis were there, and what exactly were their relationships.

Derek Barker, Local Studies Library volunteer

Further Reading

George Ingle, Yorkshire Cotton: the Yorkshire Cotton Industry, 1780-1835: Carnegie Publishing, 1997.

A very readable introduction although there is no mention of any mills in Dubb.

Colum Giles & Ian H Goodall, Yorkshire Textile Mills 1770-1930: RCHME & WYAS, 1992.

A beautifully illustrated general guide but one that does not answer any of my questions.