This is a heartwarming autobiography from former professional Keighley Rugby League player, David “Pete” Adamson, now living in Texas, but still following “the passing game”, that has been such an influence on his Keighley youth, career in the armed forces and as a trainer in his retirement years.

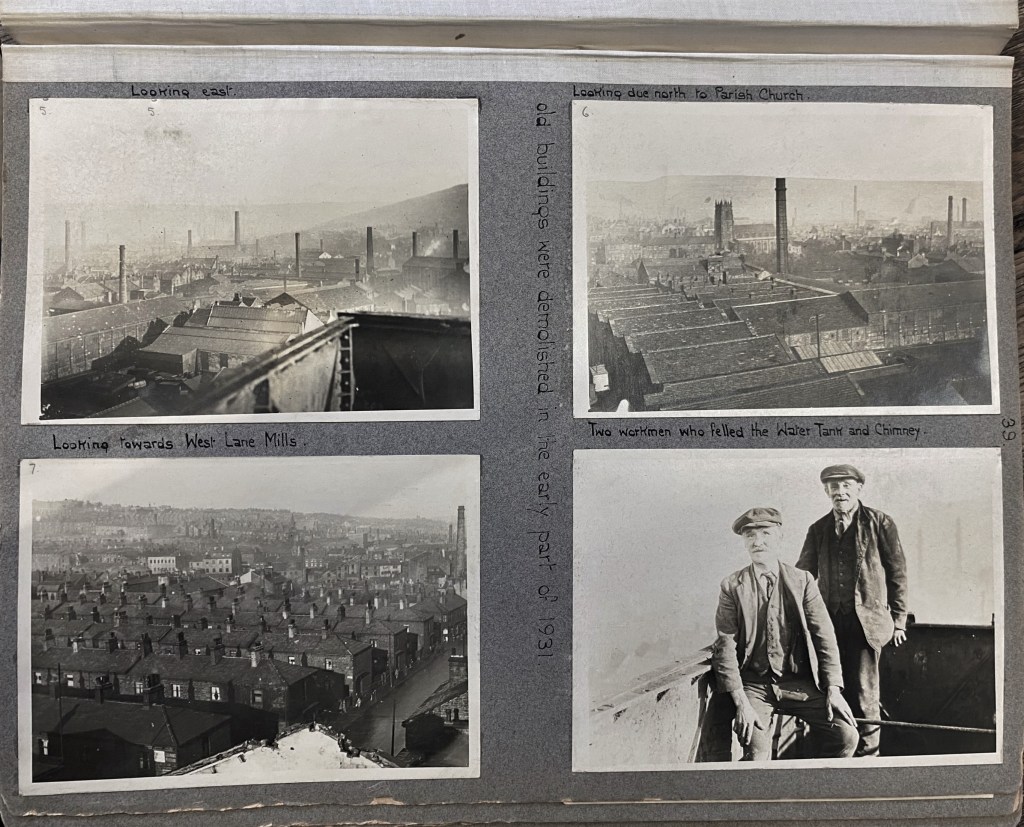

Both David’s parents were from Keighley and though he was born in Wath-on-Dearne in 1942, he returned to Keighley with his mother after the early death of his father. His mother, Mary, was one of ten children and had taken work in the local Keighley mill from the age of 11, crawling under the machinery to pick up bobbins that had fallen on the floor. On returning to Keighley, she returned to the textile trade with a job at Knowle Mill (formerly Heaton Mill) to support herself and her son.

David’s father, Sidney, had played rugby in Keighley and his influence led to David’s lifelong passion for the game. This is a story of hard times and good and how the game supported him and brought joy into his life, even during his army service abroad. David writes about his times as a player for Keighley Albion Amateur Rugby League Club and his professional play for Keighley RLFC.

The book is dedicated to his lovely wife, Miriam, who, when they recently lived over here in Haworth for a while, volunteered in Keighley Local Studies Library. Miriam even joined us recording her research into stagecoach travel from Keighley in the 19th century, it’s still available, check it out on this website:

https://bradfordlocalstudies.com/2019/11/14/christmas-day-and-the-keighley-stagecoach/

Miriam also produced an index of Brontë images that is used by staff and customers alike. https://bradfordlocalstudies.com/2019/03/12/bronte-images-116-years-of-bronte-studies/

Thanks once again Miriam and David for the generous donation of books to Keighley Library.

The Courage of his Convictions: The Life and Work of George Demaine

by Colin Neville (ISBN: 978-1-0682899-0-3)

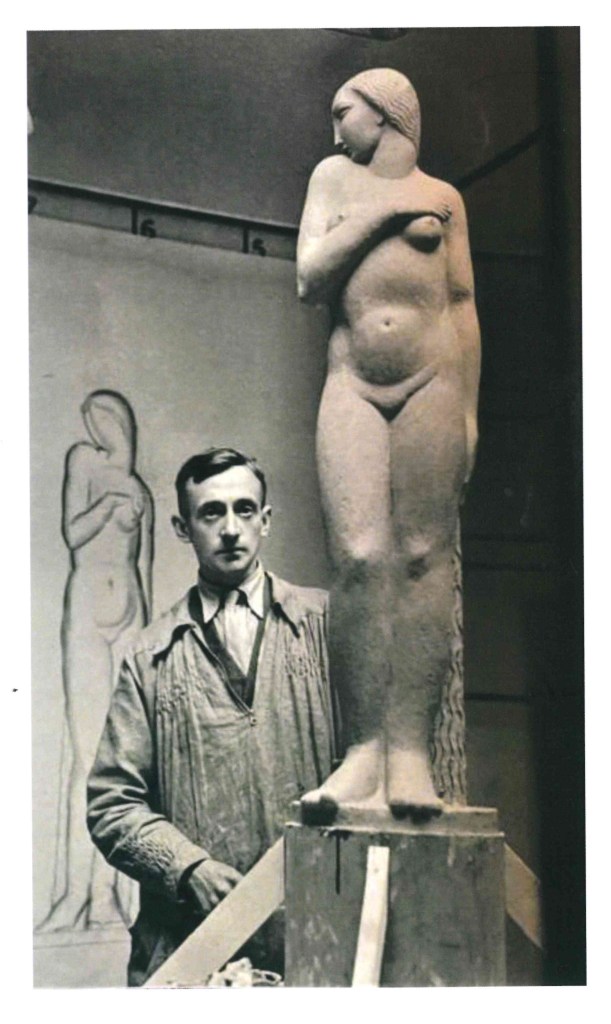

This fully illustrated book is number eleven in the Not Just Hockney series of books on the work of past artists in the Bradford district. The full list of titles can be found on the Home page of the website at www.notjusthockney.info Keighley Local Studies Library presently has 2 copies available for loan, more to follow soon.

George Frederick Demaine was a committed Methodist, husband and father; a talented painter, sculptor, model-maker, film set designer. He received his initial training at the Keighley School of Art at the Mechanics’ Institute. As a Conscientious Objector during World War One, he was imprisoned.

Colin Neville goes on to say,

“For those men that enlisted or were conscripted into the armed services, their courage came, not so much in their enlistment or acceptance of conscription into the services, but how they responded later. Their courage came from standing alongside their comrades once the real bloody horror of this war was exposed to them. Millions paid the ultimate price for this.

For George Demaine, the nature of his courage was to stand firm to his principals; principals that shunned participation – in any way, shape or form – that served this particular and pointless war. This was a courage in the face of open, bitter and sustained hostility from all sides.

But unlike the Fallen of the Great War, George lived. He lived to become a creative member of society in general, and in particular during World War Two, when he used his artistic talents to save lives and property from enemy bombing. Commitment, courage and talent of the type displayed by George Demaine always deserves recognition and its place in history.”

As usual, for Not Just Hockney publications, the book is beautifully illustrated, this time with kind permission from John Demaine, grandson of George Frederick Demaine.